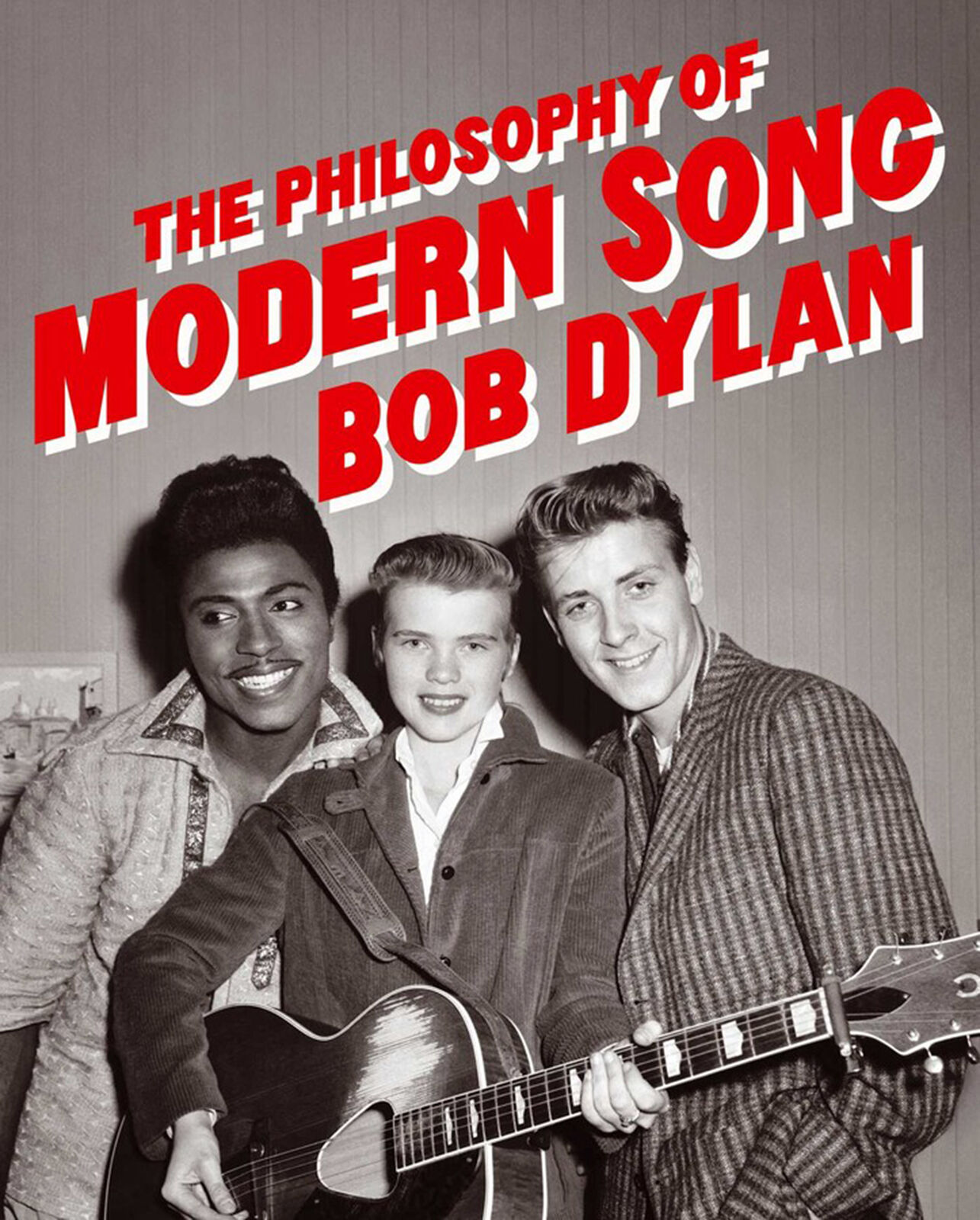

”The Philosophy of Modern Song” by Bob Dylan; Simon & Schuster (338 pages, $45)

———

Bob Dylan has thrown us another curveball.

Surprise. Surprise.

His third book, “The Philosophy of Modern Song” (Simon & Schuster, $45), promised to offer Dylan’s insights into the nature of popular music. The breezy book is more like a late-night, old-school, once-hipster DJ riffing on dozens of songs you may or may not know.

The Nobel Prize winner for literature (for his songs, not his prose) has given us a 338-page, photo-heavy hodgepodge that is part criticism, part social commentary, part pulp fiction, part comedy, part rebaked Wikipedia, and, indeed, part philosophy.

It’s informative, sometimes fascinating, occasionally insightful, generally entertaining and, of course, totally Dylanesque.

In the book, contemporary music’s greatest songwriter offers his take on 66 tunes, ranging from Stephen Foster’s not-exactly-modern “Nelly Was a Lady” (1849) to Warren Zevon’s “Dirty Life and Times” (2003). Dylan tackles pieces by big names like Little Richard, Ray Charles, the Who, the Clash and Cher, as well as standards and blues, bluegrass and country numbers.

Dylan’s short essays sometimes read like pulpy two-page movie treatments inspired by the lyrics. But that kind of imaginer is probably not what readers expect from this book.

The Hall of Famer riffing in prose often is as appealing — and enigmatic — as his riffing in music.

Commenting on the Eagles’ “Witchy Woman,” he warns whoever encounters her: “Let me tell you brother, better watch yourself. You were once a diamond in the rough, had a clear conscience and clean hands — now you’re a self-admiring unchivalrous worthless fellow with an evil nature — the scum of the earth and she’s had it up to here with you. What are the odds you’ll survive?”

Often the Minnesota icon offers background on the artist, sometimes relevant and sometimes not, gleaned by his researchers. (This feels like what he did with his “Theme Time Radio Hour” program on SiriusXM from 2006-09.) For example, in a chapter on Ricky Nelson’s “Poor Little Fool” (1958), Dylan mentions various songs about fools then talks about Nelson’s showbiz background in TV but never really discusses “Poor Little Fool.”

Occasionally Dylan gets distractingly off-key, such as when he turns a discussion of “Mack the Knife,” the Brecht-Weill song made into a smash by Bobby Darin in 1959, into a declaration on the greatness of Frank Sinatra, whom he says “just about invented the Roman Catholic Church” while Darin was an altar boy. Or when Dylan’s discourse on “Viva Las Vegas” becomes all about Elvis Presley’s conniving manager, Colonel Tom Parker, instead of the song.

Sometimes, though, Dylan analyzes a tune or the recorded version of it. For instance, he explains that Johnny Cash’s “Big River” (1957) is a takeoff on Woody Guthrie’s “The Biggest Thing That Man Has Ever Done,” and the key element to Cash’s ditty is “the chain-gang thump of the acoustic rhythm guitar.”

In his critique of “Blue Moon,” (the Rodgers & Hart piece recorded by Dean Martin in 1964), the bard observes “the simplicity of the lyrics makes it universal with enough detail to rescue it from being generic.”

Dylan, a noted borrower of melodies from folk and blues, offers lists of pop songs based on classical melodies, including “Can’t Help Falling in Love,” and songs with English lyrics based on foreign melodies, including “Beyond the Sea.”

In his randomly arranged, freewheeling book, Dylan makes all kinds of curious observations.

- “Volare” (1958) could have been the first hallucinogenic song.

- “Ball of Confusion” (1970) was “one of the few non-embarrassing songs of social awareness.”

- Hank Williams can sing anything and make the song his own. Willie Nelson would be “the only one who could be considered even in the same neighborhood.”

- Jerry Garcia plays guitar “like Charlie Christian and Doc Watson at the same time.”

- Putting melodies to diaries doesn’t guarantee a heartfelt song.

- Few songs made during the video age went on to become standards “because we are locked into someone else’s messaging of the lyrics.”

- “Like any other piece of art, songs are not seeking to be understood.”

- “Bluegrass is the other side of heavy metal. Both are musical forms steeped in tradition. They are two forms of music that visually and audibly have not changed in decades.”

Dylan, the critic, is mostly polite toward the artists but takes a few shots like positing that Elvis Costello’s “Pump It Up” (1978) exhausted people. “Too many thoughts, way too wordy,” writes Dylan, who has often been accused of being too wordy himself.

The Jokerman isn’t above cracking wise. After gushing that Roy Orbison’s “Blue Bayou” (1963) is a spectacular song and record, Dylan points out that when former Minnesota Twins announcer Herb Carneal saw a fastball that “blew by you” for a called strike, he declared, “Thank you, Roy Orbison.”

There’s philosophizing here, though not necessarily about a particular song. Dylan uses the chapter on Edwin Starr’s “War” (1970) as an opportunity to preach about war in what’s his longest soliloquy in the book.

Dylan turns his chapter on Elvis Presley’s “Money Honey” (1956) into a treatise on money and wealth, concluding: “Money don’t matter. Nor do the things it can buy. Because no matter how many chairs you have, you only have one ass.”

Throughout the book, the master wordsmith pens some indelible lines.

Discussing the traditional tune “Jesse James” (1928), he proclaims: “Criminals can wear badges, army uniforms or even sit in the House of Representatives.”

Writing about Johnnie Taylor’s “Cheaper to Keep Her” (1973), he opines: “Marriage without kids is two ‘friends with benefits and insurance coverage.’”

Waxing on Carl Perkins’ “Blue Suede Shoes” (1956), he predicts: “Carl wrote this song, but if Elvis [Presley] was alive today, he’d be the one to have a deal with Nike.”

“The Philosophy of Modern Song” is not the long-promised sequel to 2004’s “Chronicles: Volume One,” Dylan’s formidable but not comprehensive, scattershot memoir. (His first book was the prose poem “Tarantula,” published in 1971.) And this new effort is not likely to lead to any distinguished literature awards. But it could take Dylan back to the top of the charts — the bestselling book lists, that is.

Jon Bream writes for the Star Tribune.