A bill being introduced today by four Democratic lawmakers would grant college athletes sweeping rights to compensation, including a share of the revenue generated by their sports, and create a federal commission on college athletics.

The College Athletes Bill of Rights is sponsored by U.S. Senators Corey Booker (D-N.J.), Richard Blumenthal (D-Conn.) and Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.), and U.S. Rep. Jan Schakowsky (D-Ill.). If passed it could wreak havoc with the NCAA’s ability to govern intercollegiate athletics, and the association’s model for amateurism.

The announcement comes a day after the Supreme Court agreed to review a court ruling the NCAA says blurs the “line between student-athletes and professionals” by removing caps on certain compensation that major college football and basketball players can receive

The NCAA has turned to Congress for help as it works toward permitting athletes to earn money from endorsements and sponsorship deals, while also trying to fend off myriad state-level bills that would undercut any attempt to create uniform rules for competing schools.

Last week, U.S. Sen. Roger Wicker (R-Miss.), chairman of the Senate Commerce Committee, introduced a bill that would allow college athletes to be paid for their names, images and likenesses, with oversight from the Federal Trade Commission. The bill also protects the NCAA from future antitrust challenges to its compensation rules.

Booker and Blumenthal’s bill, however, goes way beyond NIL rights for athletes and is not nearly as NCAA-friendly.

“As a former college athlete, these issues are deeply personal to me,” said Booker, who played football at Stanford. “The NCAA has exploited generations of college athletes for its own personal financial gain by preventing athletes from earning any meaningful compensation and failing to keep the athletes under its charge healthy and safe.”

The legislation would allow college athletes to earn money off their names, images and likenesses with minimal restrictions, through either individual or group licensing deals.

It would also require schools to share 50% of the profit from revenue generating sports such as football and basketball with the athletes after the cost of scholarships are deducted.

Some of the biggest athletic departments in the country, such as Ohio State, Alabama and Texas, generate more than $100 million in revenue annually, the bulk of which comes from football and men’s basketball. Almost all of that revenue typically gets sunk right back into the athletic departments to pay for not just those programs, but all the other non-revenue sports.

The bill also would:

Create what it calls “enforceable” health and safety standards for athletes developed by the Departments of Health and Human Services and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention.Establish a medical trust fund athletes can access after leaving school.Guarantee college athletes’ scholarships for as many years as it takes them to receive an undergraduate degree and ban coaches and staff from influencing academic choices such as majors and courses.Remove restrictions on athletes who transfer from one school to another and penalties for breaking a national letter of intent.Require athletic departments to annually disclose revenues and expenditures, including salaries of department personnel.Establish a nine-member Commission on College Athletics that would include at least five former college athletes and individuals with legal expertise, including in the area of Title IX.

The NCAA will vote next month on legislation that will permit athletes to be compensated for their names, images and likenesses for the first time, but with some restrictions.

Athletes would not be allowed to use school logos and marks in their commercial ventures; an individual’s endorsement deals could not conflict with those of his or her school; and athletes will not be permitted to enter into financial arrangements with companies that provide services or sell goods that conflict with NCAA legislation — such as gambling, alcohol or banned substances.

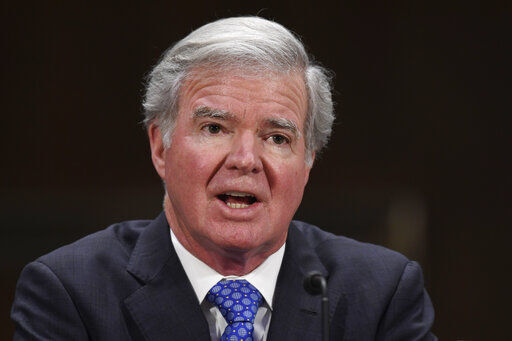

NCAA president Mark Emmert said last week the association can’t move forward with legislation until it has a “legal framework within which to do it.”

“So we need Congress to act, but we’re also trying to signal to everybody that we’re ready for this and we’re going to move forward if we possibly can,” Emmert said. “It’s the right thing to do, but we need to do it in a way that supports college athletics and it’s not destructive.”