The Bunkers weren’t just a nuclear family. They were thermonuclear.

“Meathead!” “Get outta my chair!” “Stifle!” Life in that little Queens house was explosive, and setting off most of the bombs was bigoted working stiff Archie Bunker, a proud and loud member of the not-so-silent majority.

However, his family loved him. And the genius of “All in the Family” was that audiences soon came to love all of them.

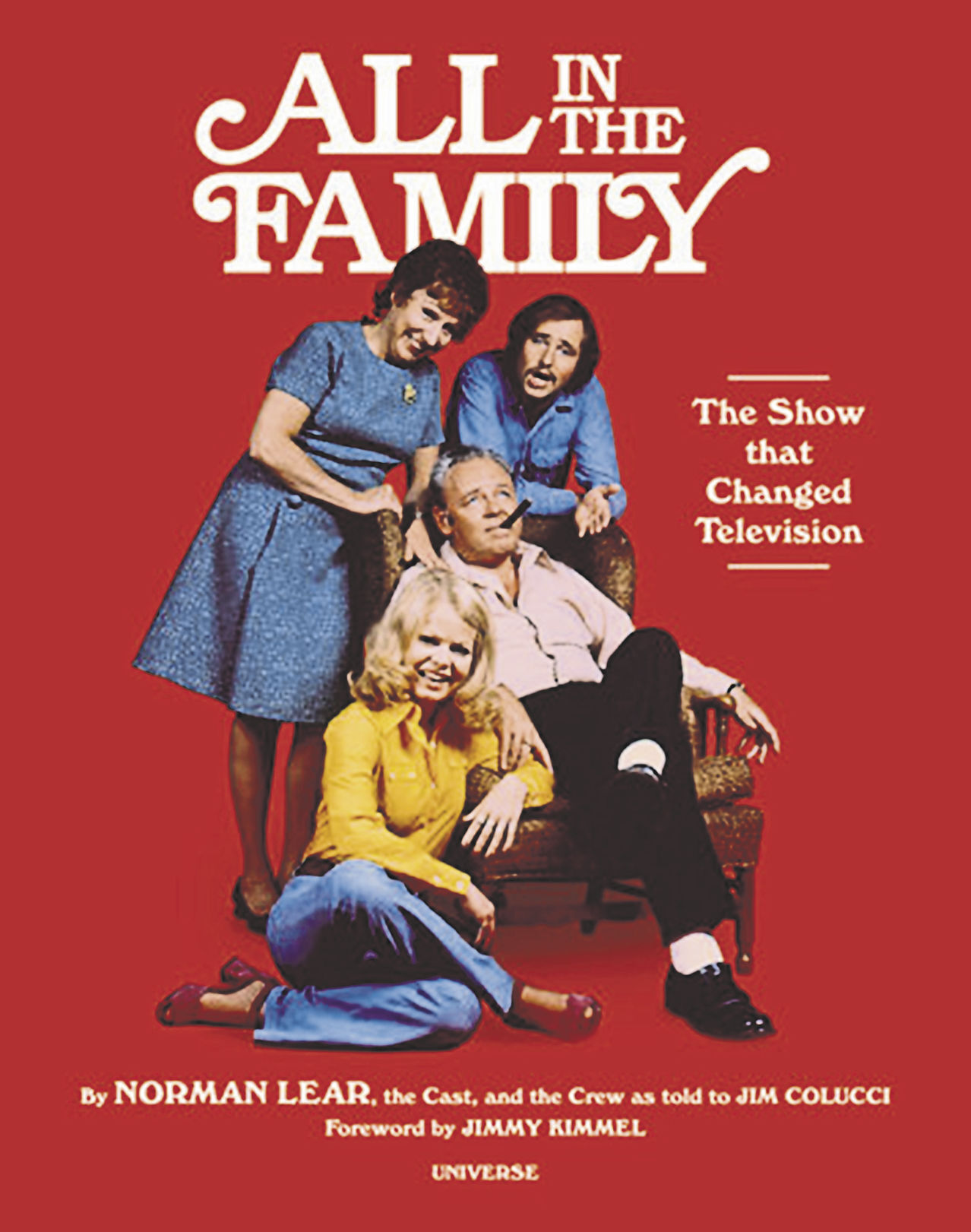

“All in the Family: The Show that Changed Television” by Norman Lear, the cast and the crew as told to Jim Colucci, and with a foreword by Jimmy Kimmel, explains why. Filled with new interviews with Lear, 99, and the surviving cast, it’s part memoir, part scrapbook and offers a rich history of how the ground-breaking show made it to the air.

And it stayed on, despite battles with the network, squabbles with its star and the pressure to stay topical in a rapidly changing culture.

It all began with Lear’s creative partner, producer and director, Bud Yorkin. In England, Yorkin caught an episode of the comedy “Till Death Us Do Part.” The main character was a right-wing dockworker named Alf Garrett, and Yorkin thought it could be reworked for American audiences.

Lear saw the show and immediately agreed it would work. He knew a family just like them — his own.

“I thought, ‘That’s my dad and me,’” Lear recalls. “My dad used to call me the laziest White kid he ever met. I’d accuse him of putting down a whole race of people just to call his son lazy, and he’d yell back, ‘That’s not what I’m doing, and you’re also the dumbest White kid I ever met.’ I knew I had to do an American version of this show.”

Once he decided, it all came together quickly.

Carroll O’Connor, a busy supporting actor, aced the audition.

“I don’t think he was off the first page before I said, ‘If we can make the deal, you’ve got the role,’” Lear recalls.

Veteran stage actress Jean Stapleton came in to read for Edith, and “Our meeting was magical,” Lear says.

They shot one pilot for ABC, “And Justice for All.” The character was then Archie Justice. It didn’t sell. They replaced the actors playing Mike and Gloria and shot another pilot, “Those Were the Days.” That also flopped.

Finally, they brought in Rob Reiner and Sally Struthers to play Mike and Gloria. They changed the family name to Bunker — a pun on “bunk,” or nonsense. They also changed the title to “All in the Family.” This pilot was sold to CBS, which scheduled it as a midseason replacement in 1971.

The network was eager to get away from its image as the home of corny, country sitcoms like “The Beverly Hillbillies.” They wanted something edgy and provocative. Except, as the premiere approached, they worried Lear’s show might be too edgy and provocative.

“They aired a huge disclaimer at the beginning,” Lear says. “Basically it said, ‘Pay no attention to the show. None of the views expressed in the show are part of what CBS thinks. If you want to watch it fine — but we wouldn’t recommend it.’ We thought it would all be over after 13 weeks.”

As the first season unfolded, CBS censors worried even more. They didn’t like Archie’s language (the profanity seemed to bother them more than the racism). They didn’t like the references to sex (the first episode had Mike and Gloria sneaking upstairs for a quickie). And they absolutely despised the Bunkers’ noisy toilet.

But Lear refused to back down; instead, he doubled down. He told the network if they didn’t like the show, he’d stop shooting it. Period. And he told his writers to push ahead, writing about things they cared about, that felt real, that mattered. So they wrote about homosexuality, about miscarriages, about integration.

“Forget about pushing the edge of the envelope,” Lear brags. “We ripped up the whole envelope.”

The show garnered seven Emmy nominations that first, short season, winning Outstanding New Series and Outstanding Comedy Series. Stapleton picked up the lead actress statue for a comedy, too. O’Connor was nominated for lead actor in a comedy but lost to Jack Klugman for “The Odd Couple.”

Now, they didn’t have to worry about cancellation.

“We knew we were a ratings hit when we started the second season,” Lear says. “But the enthusiastic reaction to the show didn’t really change anything. We all had our work to do, and it was the same work, the same struggle to come up with a good idea.”

Typically, that struggle would take them places other sitcoms avoided.

In its second season, the show did an episode about Edith going through menopause and Mike suffering from impotence. It expanded its world, bringing in characters like Cousin Maude and guest stars like Sammy Davis Jr., who brought down the house by improvising and planted an unexpected kiss on Archie’s cheek.

The notes from worried CBS executives would continue, usually along the lines of “You’re really going to do that?” Lear would continue to ignore them. You can do that when you’re No. 1 in the Nielsen ratings for five consecutive years.

People soon came to truly love the Bunkers. Archie continued to say cringe-worthy things, but he was awkwardly devoted to his wife and adored Gloria, his “little girl.”

“Archie was not a bad dude,” Lear insists.

Edith was ditsy — a “dingbat” — but the family’s rock and the show’s heart, a source of constant, unconditional love.

Americans felt they knew these people. When, in the seventh season, Archie started flirting with a waitress, the reaction from fans was swift and angry.

“I was the villain,” recalls guest star Janis Paige.

The following season, Edith was sexually assaulted in her home — and when she fought off the rapist and escaped, the studio audience cheered her on so loudly, editors had to cut the sound.

As the show went on, though, not all of Lear’s fights were with the network. O’Connor often would argue fiercely with him, almost always over the scripts. Occasionally he would threaten to walk; lawyers would get involved. At one point, during the fifth season, the actor briefly quit, and the writers began thinking of ways to kill off the character.

But O’Connor returned and stayed for all nine seasons, even as Reiner and Struthers left the show. He even went on to a spinoff, “Archie Bunker’s Place.” Stapleton eventually quit that show, yet O’Connor stayed. Archie Bunker was simply too great of a character to abandon.

Eventually, the spinoff also ended, and O’Connor went on to other projects. He died in 2001; Stapleton in 2013. But “All in the Family” lives on.

Honored with a postage stamp, it also became a Smithsonian exhibit. It gave rise to a slew of spinoffs, some memorable (“Maude,” “Good Times,” “The Jeffersons”) and some not-so-memorable (“Gloria,” “704 Hauser”).

In 2019, at Kimmel’s urging, an original script was redone on live TV with Woody Harrelson starring as Archie Bunker, and Marisa Tomei playing Edith. And the studio audience still roared — something that didn’t surprise Norman Lear at all.

“Nothing has changed,” he says. “Human nature is human nature. All these years later.”

Jacqueline Cutler writes for the New York Daily News.