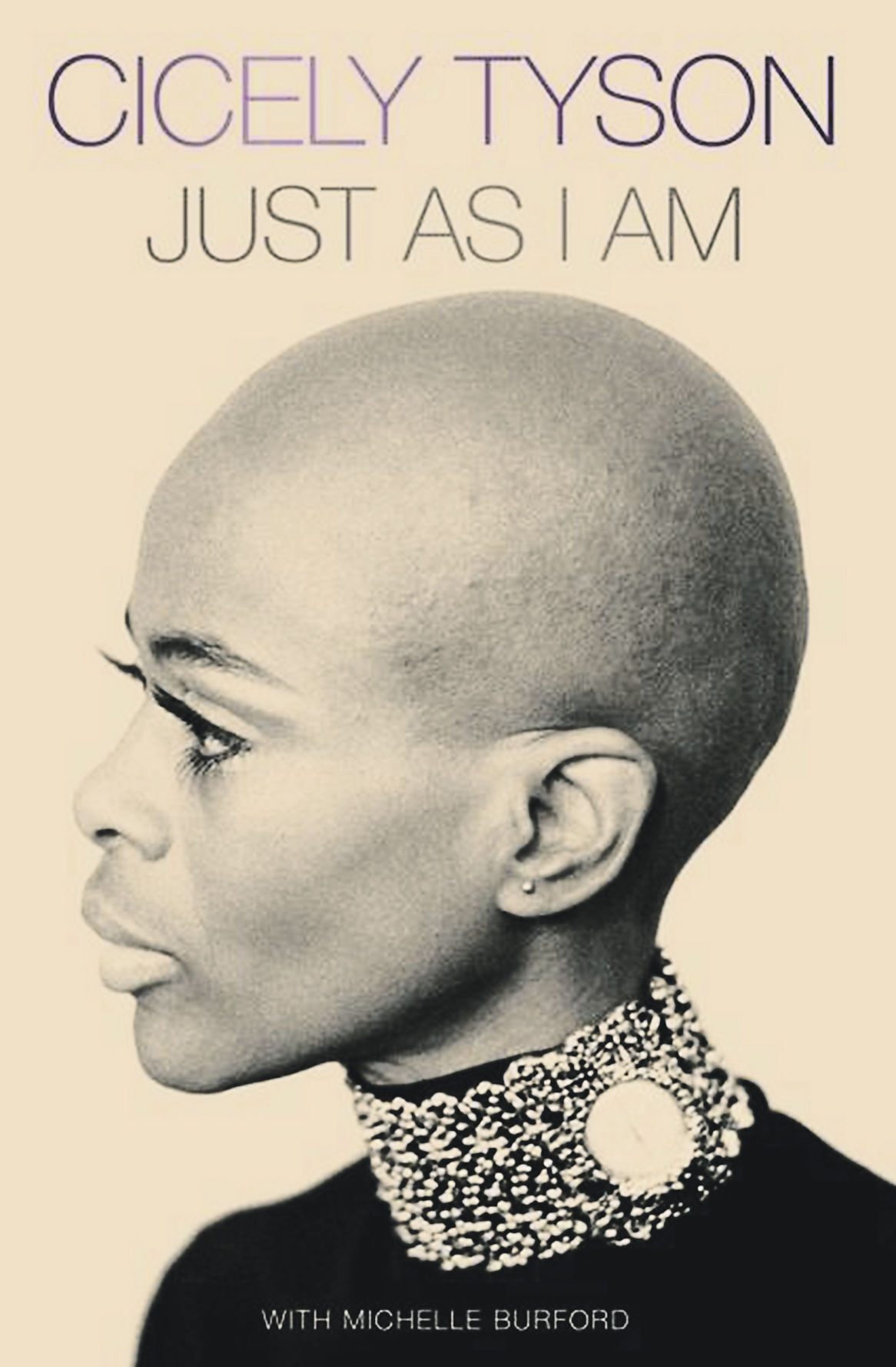

“Just as I Am” by Cicely Tyson; HarperCollins (432 pages, $28.99)

“The art of acting is the art of exposing, an emotional unveiling before others,” writes Viola Davis, in her heartfelt introduction to Cicely Tyson’s memoir, “Just as I Am.”

It’s hard to think of a better description of this book; reading it feels as if you’re sitting in Tyson’s regal presence, hearing her tell stories about her life as a Black woman in America; an Emmy- and Tony Award-winning actor; a daughter, a mother, a wife. By its end, and long before that, you’re in awe — someone truly remarkable has unveiled herself to you.

Just two days after this book’s publication, Tyson died at 96; with an actor’s impeccable timing, her work seemed finally done. But what a gift this book leaves behind. Written with Michelle Burford (named on its cover and credited as “collaborative writer”), “Just as I Am” was a long time coming.

Most memoirists don’t wait until their 90s, but Tyson knew the power of a long pause before a curtain goes up.

“Here in my ninth decade,” she writes, “I am a woman who, at long last, has something meaningful to say.”

Her true age might be a surprise for many readers: At the beginning of her acting career, in her early 30s, an agent urged Tyson to shave a decade off her official age. Only upon receiving a Kennedy Center Honor in 2015 did she widely and proudly reveal her real age: She was 90 at the time, not 80.

“For me, it was not a matter to be ashamed of,” she writes in the book. “It was a journey to delight in.”

That journey began in the South Bronx and East Manhattan, where Tyson was the second of three children born to William and Fredericka Tyson, young immigrants from the Caribbean island of Nevis. The family was poor — “a reality I see most clearly in hindsight,” Tyson writes, remembering beautiful clothes and delicious meals made by her mother, though she gradually came to realize the unhappiness of her parents’ marriage.

Though her portrait of her parents isn’t prettified — her father was a philanderer, her mother had a violent temper — it’s always loving, filtered through understanding brought by years.

She reminds her reader that her parents are part of a centuries-long story: The mistreatment of Black bodies and spirits in America, scars borne from the era of enslavement. “This is the painful history my parents were born into,” she writes. “And it is only against this backdrop that their many choices and faces can be understood.”

Growing up a skinny, quiet girl, Tyson’s talents weren’t immediately visible — though a chance to sing at church, at 7, was an early indication of a love of performance.

“All I knew was that when I was up there on that chair, my Mary Janes dangling, my voice rising up from someplace deep within me, I felt a rush. The Spirit, twisting and failing and arching its back, had shuddered through me. And as it did, my shyness vanished.”

But she didn’t become an actor until much later; a teenage pregnancy, an early marriage and clerical work took precedence for many years. Then, things happened just like in the movies: One day, at a department store, a well-dressed stranger suggested she try modeling school. Though nearly 30 and only 5-feet-4, Tyson quickly became successful at her new career and was soon offered a movie role through her agent.

At the time, she’d seen exactly one movie in her life: “King Kong,” which “scared the spit out of me. … No way was I going to get involved with the film business,” she remembered thinking. Luckily for all of us, she was quite mistaken.

“Just as I Am” takes us through Tyson’s acting training (and a horrifying assault from a prominent acting teacher) and a long career divided between stage and screen, always determined to avoid stereotypes and portray Black women with dignity and grace.

We learn about her art — “Acting, like every art form, is meant to transport its beholders, and the artist is frequently the first to make the journey” — and join her on sets: “Sounder,” for which she received an Oscar nomination; “The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman,” with the Emmy-winning performance that on some days required six hours of makeup; the phenomenon that was “Roots,” and many more. I might have wished for more about “How to Get Away With Murder,” where an electric Tyson played Davis’ mother in occasional appearances for six seasons, but that role gets short shrift; perhaps Tyson sensed by that point that time was running out.

Though her New York Times obituary notes that Tyson was generally reticent about her personal life, she’s literally an open book here, writing about her long relationship and eventual marriage to troubled jazz genius Miles Davis (“the Miles I knew was sensitive and ailing, bruised by the hurts this life metes out”), her love for the daughter whose real name she does not reveal, her friendships, her exercise routine, her joys and her griefs.

It’s a life lived in all its fullness, and reading it reveals to us — as great actors do — a complete person, one we miss once the book is closed. Doubly so now.

“We don’t have long here, children,” Tyson writes, on the occasion of Miles Davis’ death, in words that resonate all the more after her passing. “Our hopes and aspirations may feel limitless, but our days are finite, our experiences fading in the twinkling of an eye. Death is a love note to the living, to regard every day, every breath, as sacred.”

Moira Macdonald writes for The Seattle Times.