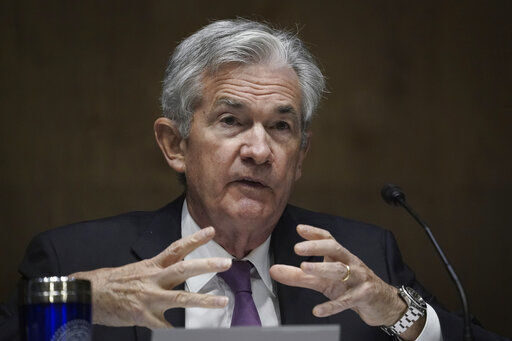

WASHINGTON — Strong financial support from the government and the Federal Reserve have spurred a solid recovery from the pandemic recession, but the rebound may falter without further aid, Fed Chair Jerome Powell warned today.

Powell said that government support — including expanded unemployment insurance payments, direct payments to most U.S. households and financial support for small businesses — has so far prevented a recessionary “downward spiral” in which job losses would reduce spending, forcing businesses to cut even more jobs.

But the U.S. economy still faces threats, and without further support those downward trends could still emerge, he said.

“The expansion is still far from complete,” Powell said in a speech to the National Association for Business Economics, group of corporate and academic economists. “Too little support would lead to a weak recovery, creating unnecessary hardship for households and businesses. Over time, household insolvencies and business bankruptcies would rise, harming the productive capacity of the economy, and holding back wage growth.”

Powell noted that the economic recovery has slowed in recent months compared with its rapid improvement in May and June. Incomes fell in August, the Commerce Department said last week. And job growth weakened in September, falling to just 661,000, less than half the gains of 1.5 million in August and 1.8 million in September.

“A prolonged slowing in the pace of improvement over time could trigger typical recessionary dynamics, as weakness feeds on weakness,” he said.

Powell has repeatedly urged Congress to provide additional stimulus, in previous speeches and in testimony before Congress. Negotiations between House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin are ongoing, but prospects for a deal appear dim.

The chairman also discussed the Fed’s new framework for its interest rate policy but did not provide any new details regarding how it will work in practice. Last month, the Fed said it was now seeking to push inflation above 2% “for some time” before lifting rates. That was a substantial shift from its previous approach, which potentially involved rate hikes once unemployment fell too low or inflation hit 2%.