A meme shared often on social media shows a picture of actor Gene Wilder as Willy Wonka from the film, “Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory.” The accompanying text reads: “Why didn’t they teach us taxes in school,” asks the guy who failed Algebra I three times.

Data compiled by the National Financial Educators Council — which reported that the average American adult lost $1,819 in 2022 because of financial errors — might confirm the lighthearted point made by the meme.

The challenge facing many consumers when it comes to personal finance and their financial literacy is nothing to laugh at, however. The Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit published by The Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Center for Microeconomic Data says total American household debt rose by 0.9% to $17.05 trillion in the first quarter of this year. That is an average of nearly $130,000 per household.

“That includes car loans, student loans, credit card debt — all that sort of stuff,” said Eric Eller, an associate professor of finance in the Francis J. Noonan School of Business at Loras College in Dubuque.

“There are a lot of people who just don’t really know what they’re getting into with their financial decisions,” Eller said.

If he had to grade people for their overall financial literacy, he said, “for an average American, it’s probably a D.”

For many people, personal finance is often a taboo subject.

“If you’re lucky, maybe your parents will share (what they know) with you,” Eller said. “And then maybe you’ll pick up more knowledge along the way.”

Local educators are responding to the gap in financial learning. The Dubuque Community School District has added a financial literacy component to its curriculum. And, at Loras, there have been conversations in the past about adding a class in personal finance as a general education requirement.

Many credit unions, banks and other organizations such as Iowa State University Extension and Outreach offer programs to help consumers improve their financial literacy.

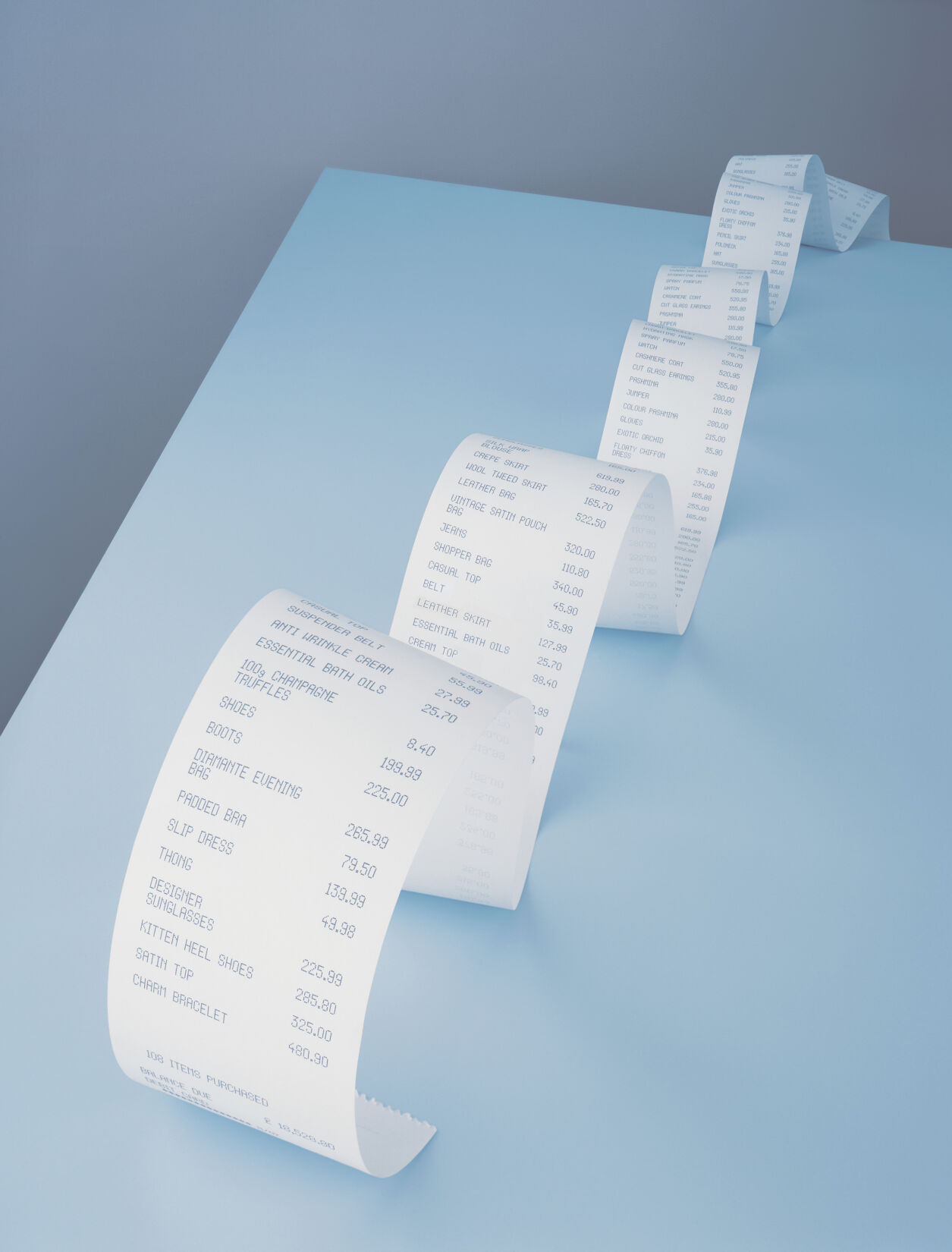

“We always try to arm people with what they need to be able to make their own smart financial choices for the future,” said Tony Viertel, community outreach and education manager at Dupaco Community Credit Union. “We’re teaching people about credit — what that means, how to use it at a young age, especially with inflation going on, how to budget, how to set aside savings. That way they don’t have to turn to us when they need a loan. They have that money set aside already.”

Dupaco offers this instructional program to anyone. Participants do not have to be members of the credit union. Dupaco also provides this service to area employers so that they can offer it as a free benefit to their employees.

Most people have — or have had — financial stress, according to Viertel.

“We see it very frequently in the workplace that people are just really struggling,” he said. “I regularly hear, ‘Boy, I wish somebody would have taught me this in school.’ That’s why it’s great we can get to these people who may think they don’t have the tools they need for a financial makeover.”

Employers also benefit when their employees improve their financial literacy.

“A lot of employees are coming with questions,” Viertel said. “A small business owner may want to help, but (offering financial advice) shouldn’t be their responsibility. We can step in and do that for them.”

Offering this type of benefit can lead to happier employees who will stay longer in their jobs.

“People are going to stay where they feel like they’re treated well and given an extra benefit that somebody else isn’t willing to give them,” Viertel said. “Going and making $1 an hour more somewhere else isn’t going to relieve the issues someone is having with their finances. Figuring out how to make the money that they already have work for them is what’s going to help.”

Eller said he often asks himself why so many Americans are financially illiterate. He also worries it’s a situation that might never noticeably improve.

“Why are we so bad at this? Why don’t we make this intentionally a part of everybody’s education,” he said. “I guess people don’t like to talk about money and they don’t want to be told what to do.

“But there’s also profit motive,” Eller said. “All the mistakes, people losing $1,800 a year because of financial errors, somebody else is making money off of that.”