Jake Ungs can’t imagine life away from Dubuque’s greyhound racing track.

“My dad bought his first dog when my mom was pregnant with me,” he said. “I’ve been coming here ever since I could walk.”

Jake, 35, works with his dad, Dave Ungs, who is the owner and founder of Copper Kettle Kennel, a longtime supplier of racing dogs for Dubuque’s Iowa Greyhound Park.

“This has always been a top dog track,” Jake said.

The final season of racing at the track started Saturday and concludes May 15. That will mark the closure of a racing venue that opened June 1, 1985, and the end of an era in Dubuque — and Iowa.

“It’s a part of history I hate to see go away,” said Bob Hardison, a greyhound owner and board member of Iowa Greyhound Association, the organization that operates the track, which is the state’s last. “It’s very sad we couldn’t find a way to keep racing going.”

A number of factors contributed to the coming end of greyhound racing in Dubuque, with some key events occurring within a few years of the facility’s celebrated debut — when greyhound racing represented a pathway out of the community’s economic doldrums of the first half of the 1980s.

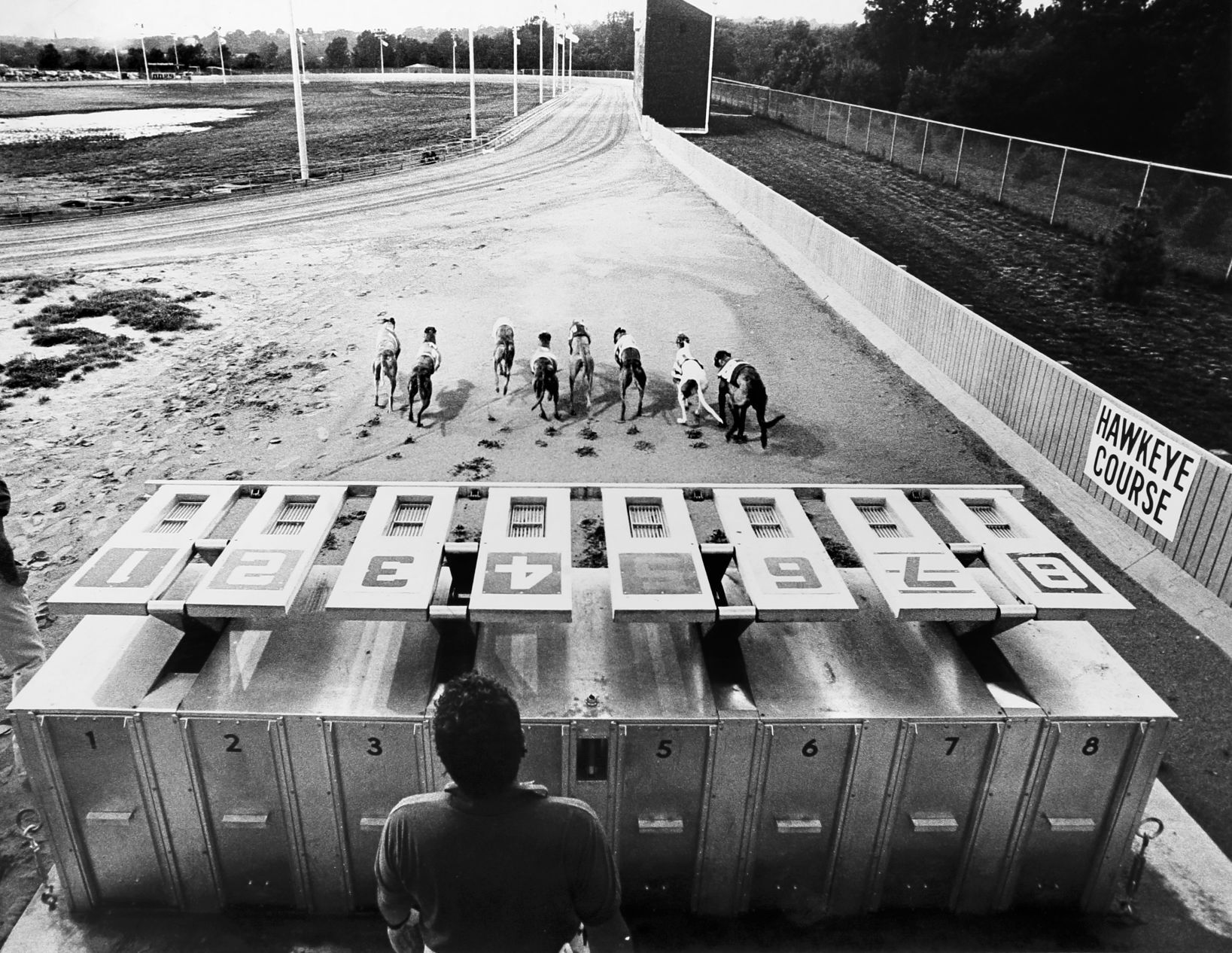

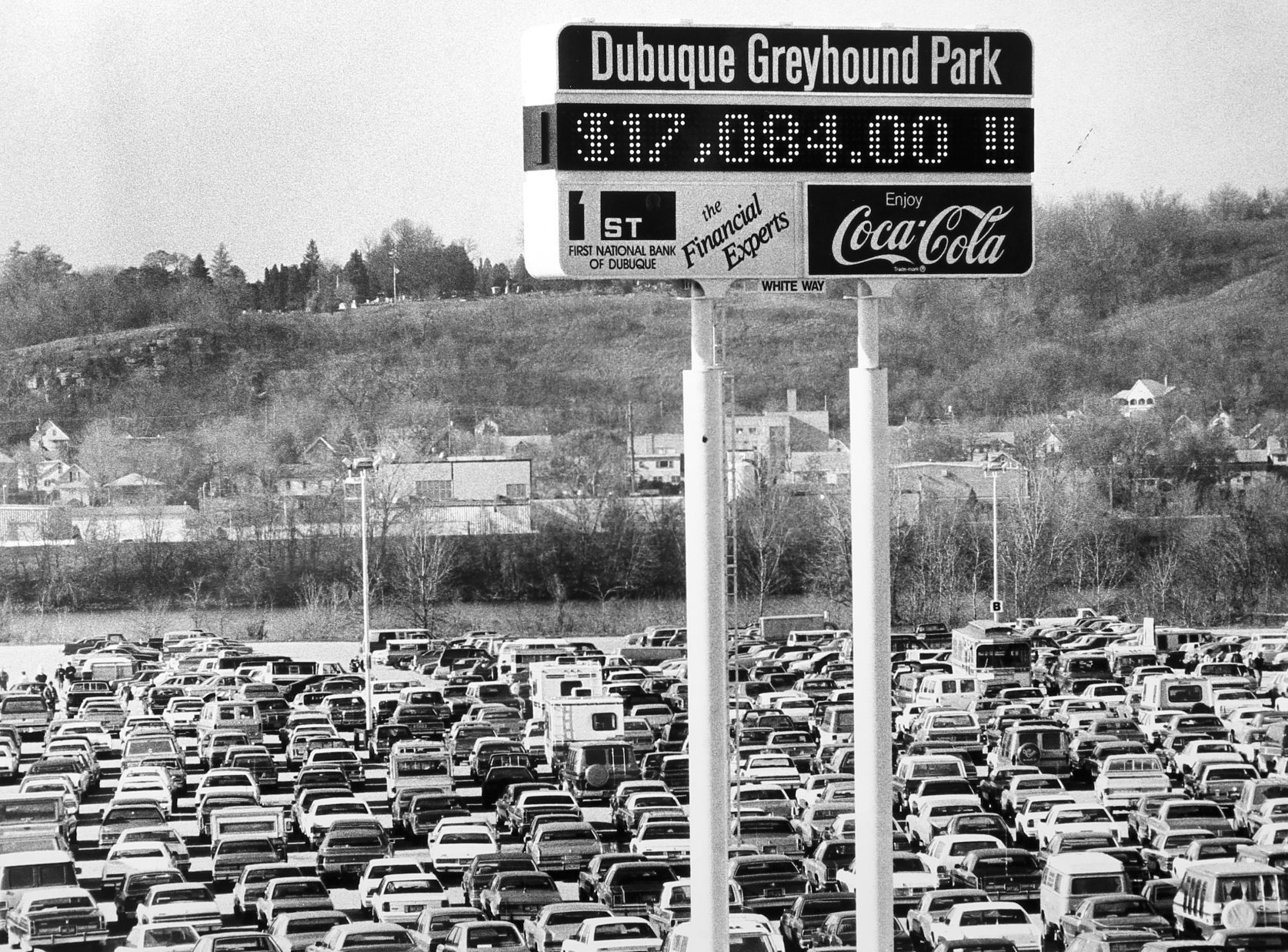

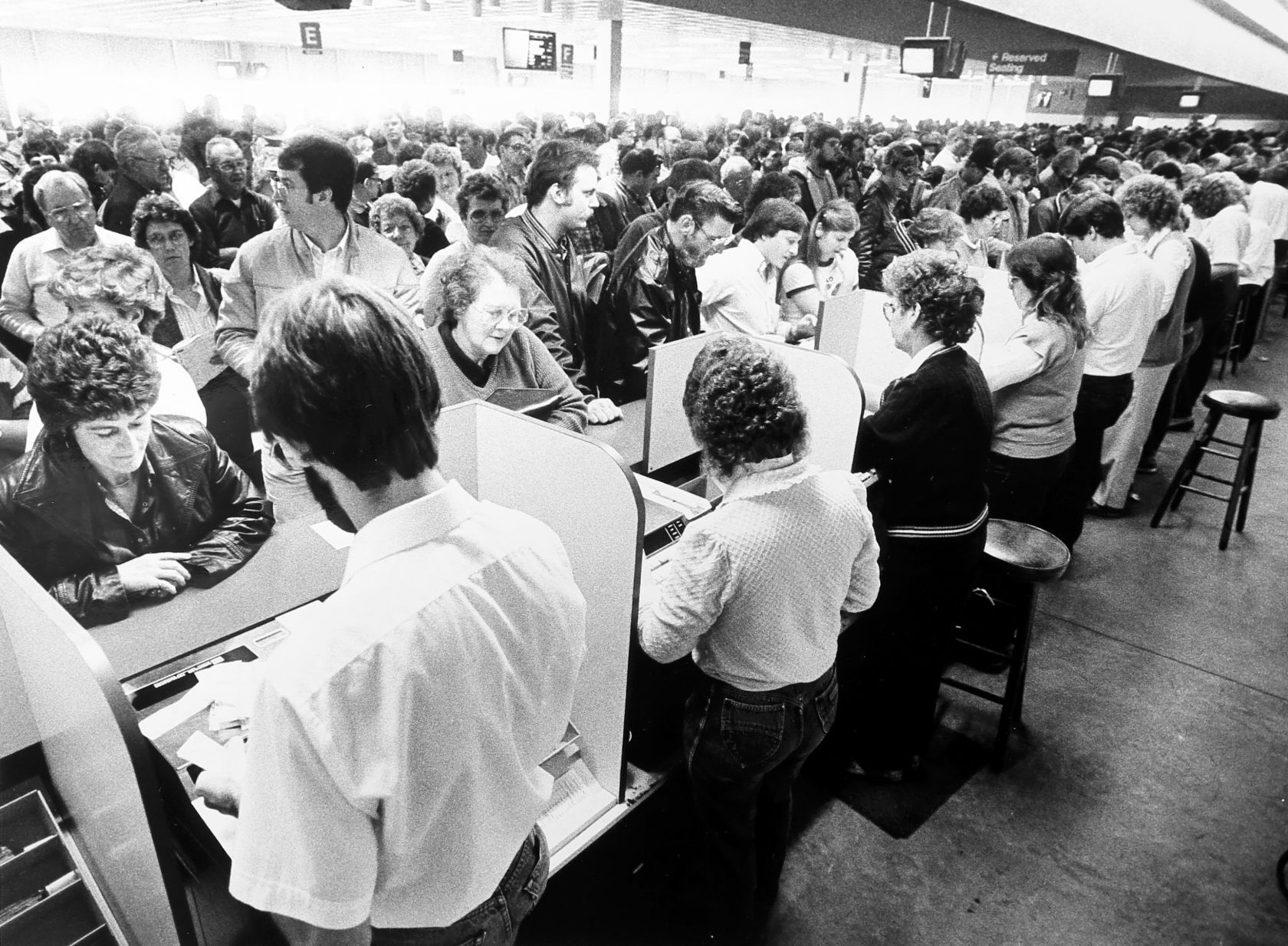

Brian Carpenter, 54, the current racing director of the track, started working at the facility in its second year of operation. He said the track drew so many patrons during its early years that the parking lot filled to capacity and the overflow parked along the nearby highway.

“They had to bring police in to direct traffic,” Carpenter said. “When we opened up, we just brought so many people from out of town — from Wisconsin and Illinois. We would have 40 buses that were parked in the parking lot on a Saturday. They were busy days.”

‘WHEN GREYHOUND RACING CAME, IT WAS HUGE’

A recession struck the tri-state area and the nation in March 1980, and job losses were particularly acute at two principal local employers, John Deere Dubuque Works and Dubuque Packing Co.

About 5,900 John Deere workers were idled during an economic slump in early 1981, and 530 jobs were lost that year at the Pack. Dubuque endured the highest unemployment rate in Iowa at 23% between 1980 and 1983, with 10% of the housing stock vacant or for sale during the period, as an increasing number of residents fled to seek new job markets in the South and West.

It was in the immediate aftermath of this local economic crisis that Iowa lawmakers approved legislation in 1984 allowing greyhound and horse racing in the state. Dubuquers were quick to recognize pari-mutuel wagering as a potential boost to the local economy, and a nonprofit community group formed to assess the potential for building a racetrack.

Voters overwhelmingly approved a $6.5-million general-obligation bond to provide the major source of funding for the track in April 1984, and the Iowa Racing Commission awarded Dubuque the state’s first pari-mutuel license that July 18. Holding the license was a nonprofit organization named Dubuque Racing Association.

Interest in the track soared, and 5,750 people applied for the 300 jobs offered at the track in the months before its June 1985 opening.

“We were the first nonprofit track in the country, and we were the first track in Iowa,” Carpenter said.

About 6,300 patrons wagered a total of $355,246 during the first two days of the track’s operations.

“When greyhound racing came to Iowa, it was huge,” Hardison said.

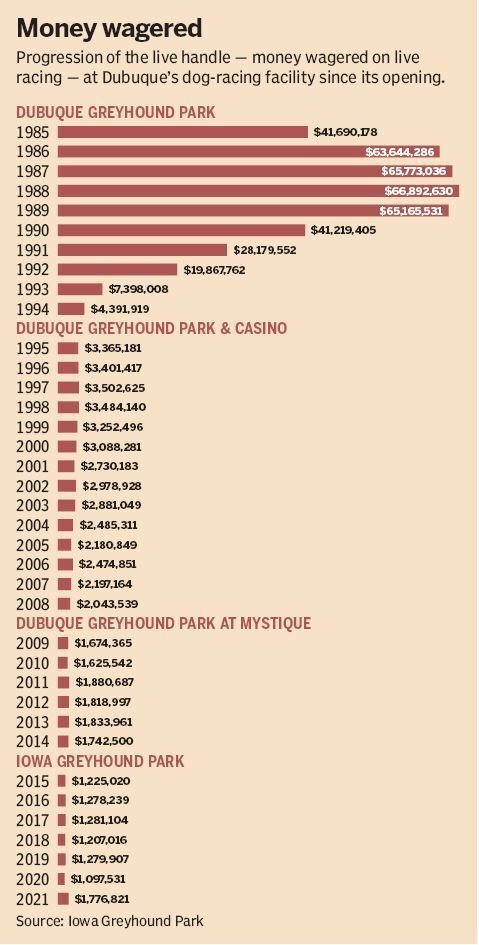

Revenue figures provided by Iowa Greyhound Park back that claim.

The opening season of racing drew 576,000 people and generated a handle – or amount wagered – of $41.6 million.

Attendance jumped to 653,000 people with a $63.6 million handle in the track’s second year, and the greyhound park’s economic boost for the city attracted national attention, with stories appearing in the Wall Street Journal, Chicago Tribune and Chicago Sun-Times.

“Everything was going really good,” Hardison said. “It really revived Dubuque and put Dubuque on the map, so to speak.”

‘WE STARTED REALLY DROPPING OFF’

Carpenter was no stranger to the track when he was named director of racing in May 1997. He had worked at the facility since 1986, when he was a 16-year-old serving as a “leadout,” escorting dogs to the starting box.

“I’ve done every job in racing,” he said recently. “I worked my way up the ranks.”

Carpenter said business continued to boom during the track’s early years, with handles of more than $60 million annually until 1990. That was the year after Wisconsin regulators approved five operating licenses for greyhound racing in that state, and bettors flocked to tracks in Geneva Lakes, Kaukauna, Lake Delton, Hudson and Kenosha.

“Our biggest groups were on Saturdays and Sundays, and they were coming from Chicago and Milwaukee,” Carpenter said of the Dubuque track’s early years. “When Wisconsin opened up those dog tracks, Kenosha cut us off from Chicago (patrons), and Geneva Lakes cut us off from Milwaukee (patrons). We started really dropping off.”

‘YOU DON’T GET ENOUGH MONEY TO COVER COSTS’

Dave Ungs, 70, of rural Dubuque County, bought his first greyhound two years after the track opened.

“She was one of the best in the country, so I bred her and that started the whole thing,” he said.

The “whole thing” is a kennel, Copper Kettle Kennel, that Ungs founded in 1993. He named the kennel after the Dubuque restaurant he operated for more than 14 years before selling it in 1994.

Ungs said his kennel now boasts 50 dogs, and he thoroughly enjoys the sport.

“With dog racing, you could come down here with $20 and stay all day,” he said.

By the time that Ungs founded his kennel, the annual handle from racing at Dubuque’s track had dropped to $7.4 million. Although the track started simulcasting out-of-town dog and horse races in 1993, that revenue only boosted the Dubuque track’s combined live and simulcast handle to $12.4 million — a far cry from the more than $60 million per year less than a decade before.

The track then moved to increase revenue by adding more than 520 slot machines in November 1995, following a referendum a year earlier in which Dubuque County voters also authorized unlimited wagers and the removal of loss limits for the Diamond Jo Casino excursion boat. Riverboat gambling had arrived in Dubuque in April 1991.

“We knew if we didn’t get a casino here, we would be done because we were competing with the riverboat,” Carpenter said.

The introduction of slots at the greyhound track marked the expansion of regional gaming opportunities.

Ungs said gambling “just exploded.”

“Everybody got slots,” he said.

The newly arrived gambling opportunities starkly contrasted with the slower, more social atmosphere of dog racing, he said.

“With dog racing, there were 15 minutes between the races,” he said. “It was a different generation that really enjoyed that (racing). Now, they have those (slot) machines that you can sit there and just keep playing.”

The Dubuque track’s annual live racing handle held steady, above the $3 million mark, for the six years beginning in 1995, while gaming proceeds from the casino offset the relatively reduced dog racing revenue.

“They had to supplement our purses because everybody knew (casino gaming) would hurt the handle at the track,” Hardison said.

Pete Temple, 64, of Monticello, Iowa, attended his first race in Dubuque in the fall of 1997 when he lived in Minnesota. He moved to Monticello the next year.

“I have been a semi-regular at the track ever since,” Temple wrote in an email to the Telegraph Herald. “On average, I attend three to four times a month during the live (racing) season, and two to three times a month when it’s simulcasting only.”

Temple admits to preferring horse racing but professed a love for the speed of greyhound racing.

“I love how hard the greyhounds try,” he said. “I love the crowd reaction as the racers near the finish. And I love having a couple bucks riding on the outcome. For me, it’s all about keeping it fun.”

By 2001, the track’s live racing handle had dropped to between $2 million to $2.9 million annually, where it remained until 2009.

‘I KNEW WE COULDN’T SURVIVE ON OUR OWN’

Dubuque’s track began live simulcasting its own races for outside consumption in 2011.

The so-called “export handle” — the money wagered at other establishments on races held in Dubuque and then simulcast — amounted to $3.2 million in 2014. However, gaming regulations limited the Dubuque track’s share of that handle to 3%.

“If that export handle (share) would have been 10% or 12%, it would have given us a chance to keep going yet, but you don’t get enough money to cover the costs (at 3%),” Carpenter said. “We get to keep between 16% and 19% of what is bet on the track (during live races in Dubuque). That’s a big difference.”

A deal approved by state lawmakers in 2014 dealt an additional, significant blow to greyhound racing in Iowa. The DRA’s casino operation, Mystique Casino & Resort — now named Q Casino and Hotel — and a casino in Council Bluffs, Iowa, reached a settlement allowing the casinos to sever ties with the greyhound industry.

As part of the deal, the Council Bluffs casino was allowed to immediately close its dog track, leaving Dubuque’s track as the last remaining in Iowa. In return, Council Bluffs agreed to pay an annual $4.6 million subsidy to Iowa Greyhound Park through 2022. Q Casino and Hotel had to pay $500,000 annually through 2021.

Carpenter said that deal severing ties cemented the Dubuque track’s eventual closure.

“When we split off from the casino in 2015, I knew we would only last eight years — that’s how long the supplemental money would last,” he said. “I knew we couldn’t survive on our own.”

Recent year statistics pale in comparison with the early years of the track. By 2019, the park’s live racing handle had dipped to $1.3 million, with a total attendance of 225,204. The pandemic year 2020 saw attendance dip to 135,044, and the handle fall to $1.1 million.

A total of 209,370 attended races last year, with a live handle of $1.8 million. The export handle leaped to $19.9 million, with the closure of the Florida tracks resulting in a dearth of live greyhound action for race fans nationwide. The track only received 3% of that simulcast handle, however, due to regulations.

‘FLORIDA GOING DOWN KILLED THE WHOLE THING’

The U.S. once boasted more than 60 greyhound tracks, and dog owners who raced during Dubuque’s summer season often traveled elsewhere to race during other times of the year.

“We went to Florida some years, and Texas and Colorado,” Dave Ungs said. “We ran at a lot of different places.”

Carpenter said Florida’s racetracks were vital for the economic viability of the sport locally and nationally.

“For people who bred dogs, if they didn’t win at this track (in Dubuque), they could try another track,” he said. “(Breeders) don’t want to put money into something if they don’t know they’re going to get their money back. In Florida, there were enough tracks where you could get your money back at a track somewhere down there.”

Economic factors and animal welfare concerns began to chip away at the number of American greyhound tracks, culminating in 2018, when Florida residents approved a constitutional amendment to eliminate greyhound racing in the state at the conclusion of the 2020 season.

“Florida going down really killed the whole thing,” Jake Ungs said. “There were 14 racetracks there. When people would breed a litter of dogs, their best couple of dogs would come here, but the lesser dogs could go down (to Florida) and compete really well there.”

Hardison, of Onawa, Iowa, has bred and raised greyhounds since 1977, and he began racing dogs at Dubuque’s track in 1990. He followed developments in Florida with interest.

“What happened down there (in Florida) was largely due to the (anti-racing) activists,” he said.

Christine Dorchak, the president of the anti-greyhound racing organization Grey2K USA, wrote in an email that she welcomes the phasing out of greyhound tracks nationwide.

“Wagering on dogs was first legalized in Florida as a shiny new way to raise state revenue during the Depression era, but by the time Iowa’s tracks opened in the 1980s, the industry had already begun its perilous collapse,” Dorchak said.

Dorchak said three factors have contributed to the reduction of greyhound tracks in the U.S.

“It’s a growing disinterest in this old-fashioned style of gambling, increased public knowledge about the fate of unwanted greyhounds and competition from other forms of gambling,” she said. “Change started to happen when people started voting with their feet — attendance plummeted, and only the lure of slot machines could bring (people) onto track properties.”

Hardison said he doubts that anti-racing advocates had much direct influence on the fate of Iowa’s greyhound tracks.

“I don’t think our state bought into some of these ‘anti’ groups,” he said. “In Iowa, it’s known that the greyhounds get excellent care and the track is prepared to be very safe for them. Our biggest problem was the casinos (severing ties). (Activists) may claim victory here, but I don’t think that’s the case.”

The end of dog racing in Florida left only four American tracks: the one in Dubuque, one in Arkansas and two in West Virginia. The Arkansas track is due to close at the end of this year.

The reduction in tracks has meant less need for racing greyhounds.

“Now, there’s a shortage of dogs,” Carpenter said. “Everybody thinks there are a ton of greyhounds out there, but there really isn’t. We normally would run 15 races (per performance), but this year we’re down to 10 races (due to the dog shortage).”

Jake Ungs said he and his dad’s kennel stopped producing new greyhound litters a few years ago.

“We knew this was going to happen years in advance, so we quit breeding them because we knew the track was going to close,” Jake said. “It’s not like we ran out of dogs so the track is closing. Everybody cut down on breeding dogs because the track was closing.”

‘SO MANY DIFFERENT OPPORTUNITIES’

The Iowa Racing and Gaming Commission in November approved a one-month 2022 season for Dubuque’s greyhound track. It features 18 race days, each with 10 races on the schedule.

“I am happy that there is going to be one last season, even though it’s a short one,” Temple said. “I am sad that after mid-May, live racing in Dubuque will no longer be an option.”

The last day of racing at the track, May 15, also is the final day that winning tickets and vouchers can be cashed in person.

“I don’t even like to think about it,” Jake Ungs said.

Alex Dixon, Q Casino’s president and CEO, said he appreciates the dog track’s legacy in Dubuque.

“Q Casino wouldn’t be here without racing (and) without the hard work of so many people in the community,” Dixon said. “But rather than lament the end of racing, we want to celebrate racing while it is still here.”

Live simulcasting of out-of-town dog and horse racing at the Dubuque track will end when it closes, and Q Casino is a possible landing spot for that form of gaming after May 15.

“We’re working hard to try to be able to provide that amenity after racing ends,” Dixon said.

The greyhound park’s grandstand is leased from the DRA, while the track itself is leased from the City of Dubuque. Dixon said the end of racing provides an opportunity to redevelop the space the greyhound park has occupied for more than 35 years.

Dixon said Q Casino has “no concrete plans” for the development of the area, although he said officials are using the Chaplain Schmitt Island Master Plan, developed by the city in 2014, as a guide for potential future options.

“We’ve got to do our homework, so that whatever we build, we do it right,” Dixon said.

The master plan outlines potential outdoor and recreational opportunities in the area, including expanding amenities at Q Casino. Dixon likened the possibilities on Chaplain Schmitt Island to the development that has occurred in the Port of Dubuque and the Millwork District.

“This is as much about the redevelopment of Chaplain Schmitt Island as it is about Q Casino,” Dixon said. “There are so many different opportunities for Q Casino and Schmitt Island. Part of what we’re working on is how we weave all of these (potential) amenities together so we can become a regional destination on the island. That’s what I’m excited about.”

‘CAN’T IMAGINE NOT HAVING GREYHOUNDS’

Dave Ungs plans to retire after the track closes. His son Jake hasn’t finalized his plans.

“Over the wintertime, I started dealing cards upstairs (at Q Casino), but I also have some job offers to train dogs in West Virginia,” Jake said. “West Virginia should have a good while (of success) yet. Wagering there has picked up a lot since the other tracks closed.”

Hardison said he will continue to raise a litter of greyhounds every year.

“I can’t imagine ever not having greyhounds in my life,” he said. “I currently have 24 here on my farm.”

Hardison had about 100 greyhounds on his farm back in racing’s heyday, when he ran his own kennel. He said he will continue to provide a few dogs to places where racing continues.

“I have sent a couple to Australia,” he said.

Temple said he is hopeful that either Q Casino or another entity will seek a license to provide racing simulcasts as part of their operations.

“I believe many of us would like to continue to enjoy simulcasting in the company of others, even after live racing is gone,” he said.

As for Carpenter, who has spent his working life at the track, he said he is unsure of his future plans.

“I promised I would do everything to get this closed and done right,” he said. “Once I do that, I will move on.”