CHICAGO — Allen Sanderson grew up in Idaho. He played high school baseball and worked for a minor league team in Twin Falls, providing a ride home for Dick Allen long before he became a feared slugger with the Philadelphia Phillies.

That’s part of how Sanderson sees baseball’s labor strife, as a longtime baseball fan. But he also follows along from a different perspective, one of a sports economist at the University of Chicago.

“What is the right division between the owners and the player? How much should the players get? How much should the owners get?” Sanderson said. “There’s no right answer to that question. There may well be to you making French fries at McDonald’s or something like that. There probably is a right answer to that question about what’s a reasonable amount in a competitive marketplace for you to earn.

“But once you’re in the sports world or the entertainment world, something like that, you know just all bets are off. It’s largely a function of how well can I negotiate our side in this.”

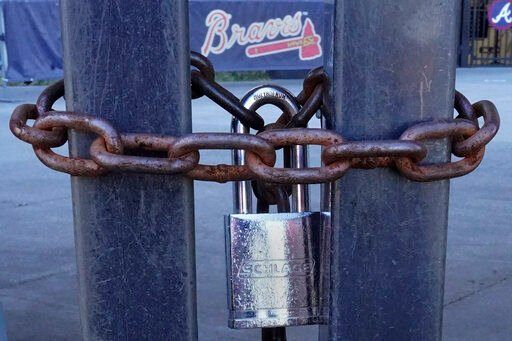

That last part isn’t going very well at the moment, not for Major League Baseball or its locked-out players.

Baseball’s ninth work stoppage reached 96 days today. It is the sport’s first labor conflict to cause games to be canceled since the 1994-95 strike wiped out the World Series for the first time in 90 years.

The sides met for 95 minutes on Sunday, largely restating their positions to each other. Negotiations broke off last week after nine days of talks in Jupiter, Fla., and Commissioner Rob Manfred canceled the first two series of the season for each team, a total of 91 games.

While the sides try to chart a path forward, hoping to get baseball back on the field, some experts in labor relations and sports business are watching the dispute from an academic viewpoint.

“I look at it through the collective bargaining lens,” said Art Wheaton, the director of labor studies in the Buffalo Co-Lab for Cornell University’s industrial and labor relations school.

“The lens, I do a lot of training for unions about negotiations and how to bargain, so anything when it comes to contract time I keep an eye on.”

Manfred, Deputy Commissioner Dan Halem and NHL Commissioner Gary Bettman each graduated from the ILR School at Cornell.

When Wheaton looks at the baseball talks, he sees a process bogged down by a complicated mix of audiences that includes big- and small-market owners, players with a wide range of salaries and agents attempting to indirectly influence the negotiations from afar.

“If you can make it collective bargaining where everybody on the company side and everybody on the union side are trying to solve the difference, that’s a whole lot better than having all of the different owners pushing their own buttons and all of the different agents also trying to change it,” said Wheaton, a Cincinnati Reds and Boston Red Sox fan who follows baseball more closely when it gets to the postseason.

“Collective means working together, and that I think is what has broken down here.”

Wheaton also took issue with what he called “deadline bargaining,” waiting until the last minute for substantive negotiations in hopes of creating big movement. After Major League Baseball locked out its players in early December, the sides didn’t meet again until Jan. 13.

“It’s not an unusual tactic. I just don’t find it a very helpful tactic,” he said. “You add a lot of extra stress and high risk, which some people like because it forces the other side to make a decision. But it’s not always the best way to make a good, rational economic decision by waiting until the last minute, throwing all these numbers around.”

The long-term effect of the lockout remains to be seen. It took baseball years to recover the last time it canceled games because of a labor action, and Manfred is likely to wipe out more of the schedule if there isn’t a resolution soon.

“I think that what baseball is doing is turning off the casual fan and turning off the young fan,” said Stephen Greyser, a marketing and communications professor in the Harvard Business School and a a longtime Red Sox season-ticket holder.

“The reality is those people are not going to be getting any more interested in going to games or watching games on TV by not having games at all and not having the season start.”