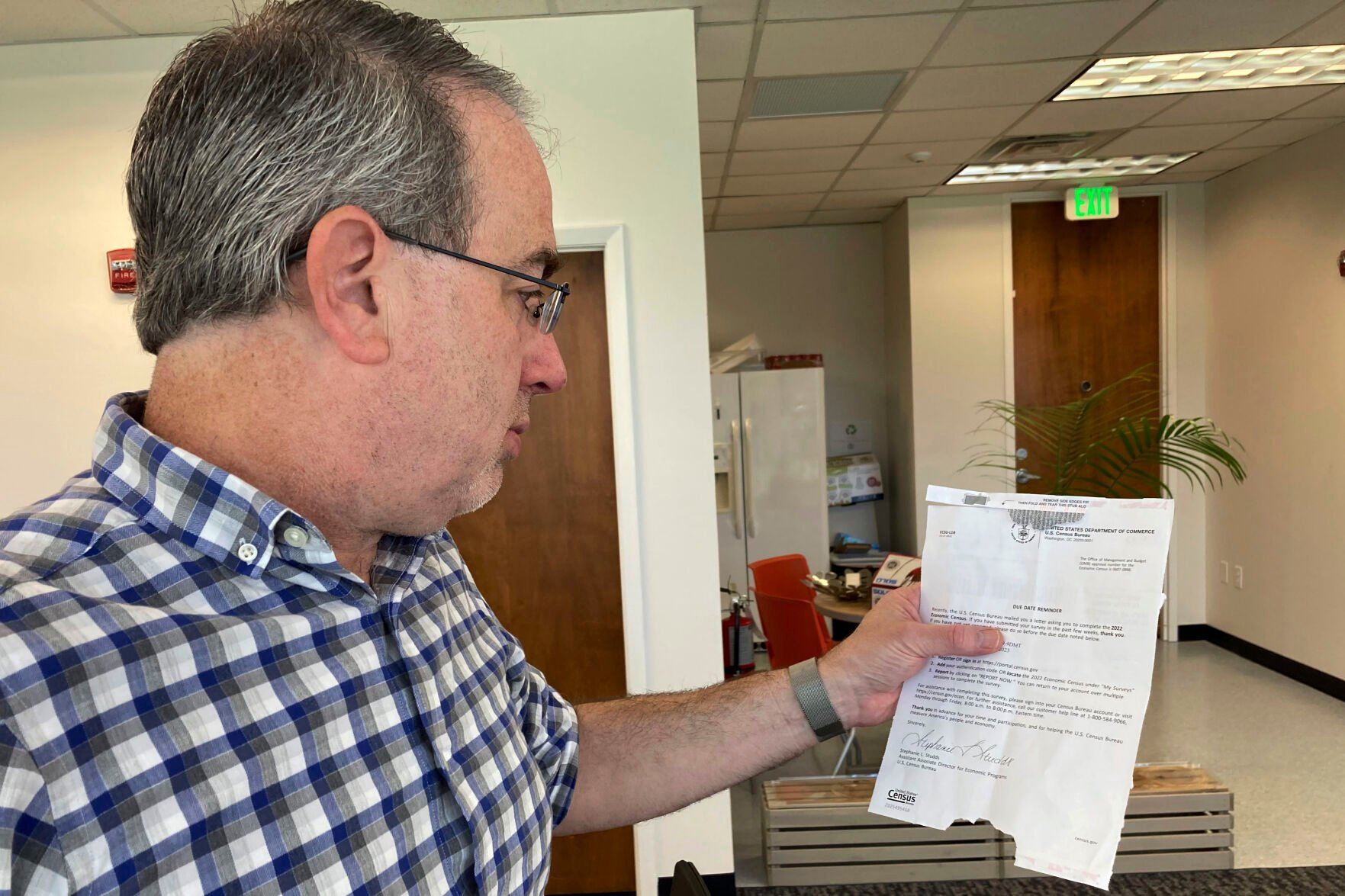

ORLANDO, Fla. — Erik Paul didn’t mind answering government questions about where his software development business was located or how many employees it had. But when queries from the U.S. Census Bureau broached the company’s finances, the chief operating officer hesitated.

“When you start asking financial questions, I get a little squirrelly,” said Paul, of Orlando, Fla., who recently responded online to the 2022 Economic Census.

It’s a problem the Census Bureau and other federal agencies are facing as privacy concerns rise and online scams proliferate, lowering survey response rates in the past decade. The pandemic exacerbated the problem by disrupting in-person follow-up visits.

Low response rates introduce bias because wealthier and more educated households are more likely to answer surveys, which impacts the accuracy of data that demographers, planners, businesses and government leaders rely on to allocate resources.

Survey skepticism has grown so much that the Federal Trade Commission this month put out a consumer alert reassuring the public that the American Community Survey, one of the Census Bureau’s most vital tools, is legitimate.

The ACS is the bureau’s largest survey and asks about more than 40 topics ranging from income, internet access, rent, disabilities and language spoken at home. Along with the census, it helps determine how $1.5 trillion in federal spending is distributed each year, where schools are built and the location of new housing developments, among other things.

Though it’s considered the backbone of data about the U.S., the survey’s response rate fell to 85.3% in 2021 from 97.6% in 2011, while other federal questionnaires have fared even worse.

Wariness is understandable, the FTC alert said, but the information being sought serves a vital public purpose.

“The ACS is a legitimate survey to collect information used to make decisions about how federal funding is spent in your community,” the FTC said in the alert posted on its website.

Skepticism can be hard to dispel. It persists even among those charged with protecting the public against identity theft and helping them with online security.

In the comments section of the Federal Trade Commission’s website, Cherie Aschenbrenner responded to the consumer alert by writing: “There is NO WAY in anyone’s right mind should they answer these invasive questions. 20 pages of them! NO WAY!!!!”

Aschenbrenner is an elderly services officer with the police department in Elgin, Ill. Part of her responsibilities include warning the elderly about potential scams.

In an email, she said her comment was a personal opinion and that she didn’t want to elaborate.

“Probably not in my best interest, professionally,” she said.

Declining response rates can be blamed on survey fatigue consumers suffer from things like answering questions when they purchase products, as well as privacy concerns and the amount of time it takes to answer queries. Surveys also reach fewer people because of spam filters, caller ID and doorbell cameras, said Douglas Williams, a senior research survey methodologist at the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

“What is most unique about the past decade, aside from COVID, is the magnitude of the decline,” Williams said. “It is difficult to pinpoint any one reason or cause, but technology is a likely candidate.”

Federal statistical agencies have tried sending advanced and follow-up notices, making follow-up calls and visiting households that don’t respond. They’re also allowing respondents to answer via different modes, such as internet, mail or phone. Some have even offered money to get answers about how much people earn.

Officials are also looking for alternative data sources, such as administrative records collected by government agencies like the Social Security Administration and the Internal Revenue Service. They also are looking to capture and aggregate real-time financial transactions, such as soda purchases at a grocery store. The details are still being worked out on that, but they will include privacy protections preventing any particular purchase from being attached to an individual consumer.

The Census Bureau, which conducts more than 130 surveys and related programs each year, already is taking steps toward using more administrative records. This month the bureau proposed using existing records on property acreage instead of asking about it on the American Community Survey. It’s also examining how to leverage other sources for information about housing.

The bureau’s surveys cover all kinds of topics, including retail expenses, housing costs, school system finances and how people use their time.

Relying more on administrative records can free up resources so more effort can be spent on trying to reach hard-to-count populations, such as immigrants, rural area residents and people of color, Census Bureau Director Robert Santos said.

Such populations can be difficult to count because of language barriers, lack of internet access, distrust in government or because individuals are just plain hard to locate. But people face losing out on resources if they’re not tallied or interviewed.

The 2020 census was the first time in the nation’s once-a-decade head count that administrative records were used to fill in gaps about households with missing information. A post-count evaluation that surveyed a portion of the population and compared those results with the census figures showed information from the Social Security Administration and the IRS was more accurate than interviewing neighbors or landlords, the traditional method employed when a household doesn’t respond.

“Why can’t we more quickly rely on administrative records that have actually been shown to be able to count a large proportion of our population?” Santos asked. “That saves money.”