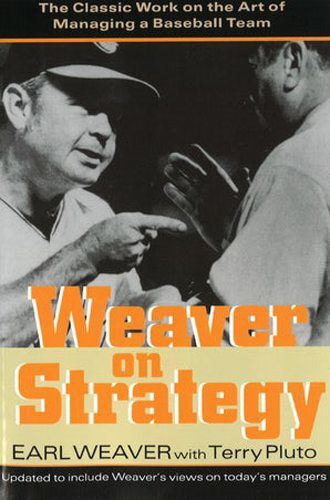

“Weaver on Strategy: The Classic Work on the Art of Managing a Baseball Team” by Earl Weaver; Potomac Books (202 pages, $19.95 paperback)

Nike unveiled the “Chicks Dig the Long Ball” advertising campaign in 1999, one year after the home run chase between Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa.

Fifteen years earlier, Hall of Fame manager Earl Weaver’s 1984 book, “Weaver on Strategy,” documented the popularity and importance of the home run, which remains a primary source of offense in an increasingly data-driven game.

As the 2020 baseball season finally gets ready to resume after the coronavirus delay, Weaver’s book provides a refresher course on the preparation and intricacies of a baseball season — as well as an amusing chapter on umpiring and why arguing belongs only to the manager.

Many of Weaver’s themes in the 196-page book, co-authored with Cleveland sports columnist Terry Pluto, hold firm despite the game’s increasing reliance on specialization since Weaver’s second retirement after the 1986 season.

Many of Weaver’s Baltimore Orioles teams were blessed with home run hitters — from Frank Robinson and Boog Powell during his early years to Eddie Murray, Cal Ripken Jr. and the platoon of John Lowenstein and Gary Roenicke at the end of his first tenure as Orioles manager (1968-82). That philosophy helped him win four American League titles and the 1970 World Series.

Weaver’s mission extended to a young Don Baylor, who eventually developed into a power hitter by “looking to hit the 2-0 and 3-1 pitches out of the park,” Weaver wrote. “It took a little time, but (Baylor) eventually became the 25-30 home run man I knew he could become.”

Weaver’s disdain for the bunt lay in the fact there are only 27 outs in a game.

“You play for one run — that’s all you get,” Weaver wrote.

The suddenness of a home run appealed to Weaver, who died in 2013 at 82.

“The minute you hit a home run, no questions asked,” Weaver wrote. “With anything else, you aren’t guaranteed a run.”

And it doesn’t matter where the home runs come from. The platoon of Lowenstein, Roenicke and Benny Ayala produced 36 home runs and 102 RBIs from left field in 1982, the result of Weaver not believing one player could do the job on a daily basis and opting to maximize their skills.

Weaver preferred carrying bench players with multiple tools and leaned toward an offensive-minded bench because those players were more likely to be used in pinch-hitting situations or to spell a struggling starter. He kept unheralded Glenn Gulliver on his 1982 roster because of his history of drawing walks and even batted Gulliver second on occasion when Ken Singleton was struggling.

Weaver gained acclaim for managing four 20-game winners in 1971 — Jim Palmer, Mike Cuellar, Dave McNally and Pat Dobson — and he revealed in the book his involvement in some of their acquisitions and how he passed along tips about opposing hitters.

“It comes down to recognizing ability, and that has always been my strong suit,” Weaver declared.

Of more help to potential pitching coaches and managers is Weaver’s chart on seven ways of telling if a pitcher is losing his edge, from paying attention to the flight of foul balls to the consistency of his delivery.

Weaver’s three objectives of spring training hold true: For players to condition their bodies and minds for the challenge of a 162-game season, for workouts and games to sculpt the 25-man roster and for veterans to review fundamentals and newcomers and rookies to learn his preferred style of play.

His nine cliches of spring should be posted on the wall of every spring training media workroom. “Patience! It’s a long way from the Grapefruit League,” Weaver responded to a writer declaring that a minor-league outfielder was destined for the Hall of Fame based on a few hard-hit balls during an intrasquad game.

Chicago White Sox analyst Steve Stone, who won the 1980 AL Cy Young Award with the Orioles, said Weaver was by far the best manager he played for, partly because Weaver had a knack for getting Stone to pitch his best in spite of his manager.

Weaver, however, was very complimentary of Stone in the book, crediting him for recognizing immediately that the Orioles were a “we” team and for Stone’s ability to adjust during the middle of his career and throw more high fastballs that fooled batters looking for his curve during his 25-win season in 1980.

An epilogue, based off a 2002 interview with Baseball Prospectus, revisits Weaver’s 10 Laws that he sprinkled throughout the original version of the book.

Twenty-five years after teams shifted to five-man rotations, Weaver was a staunch believer that four-man rotations would work. That’s not likely now, with teams protecting pitchers with strict pitch counts and some using “openers” that require more relievers.

But nearly all of Weaver’s theories on running a team and operating a game hold up in a game that has advanced from his 3-by-5 index cards to binders of game-day data.

Mark Gonzales writes for the Chicago Tribune.