It was a particularly good year for excellent books and 10 is way too few. In order of authors’ names:

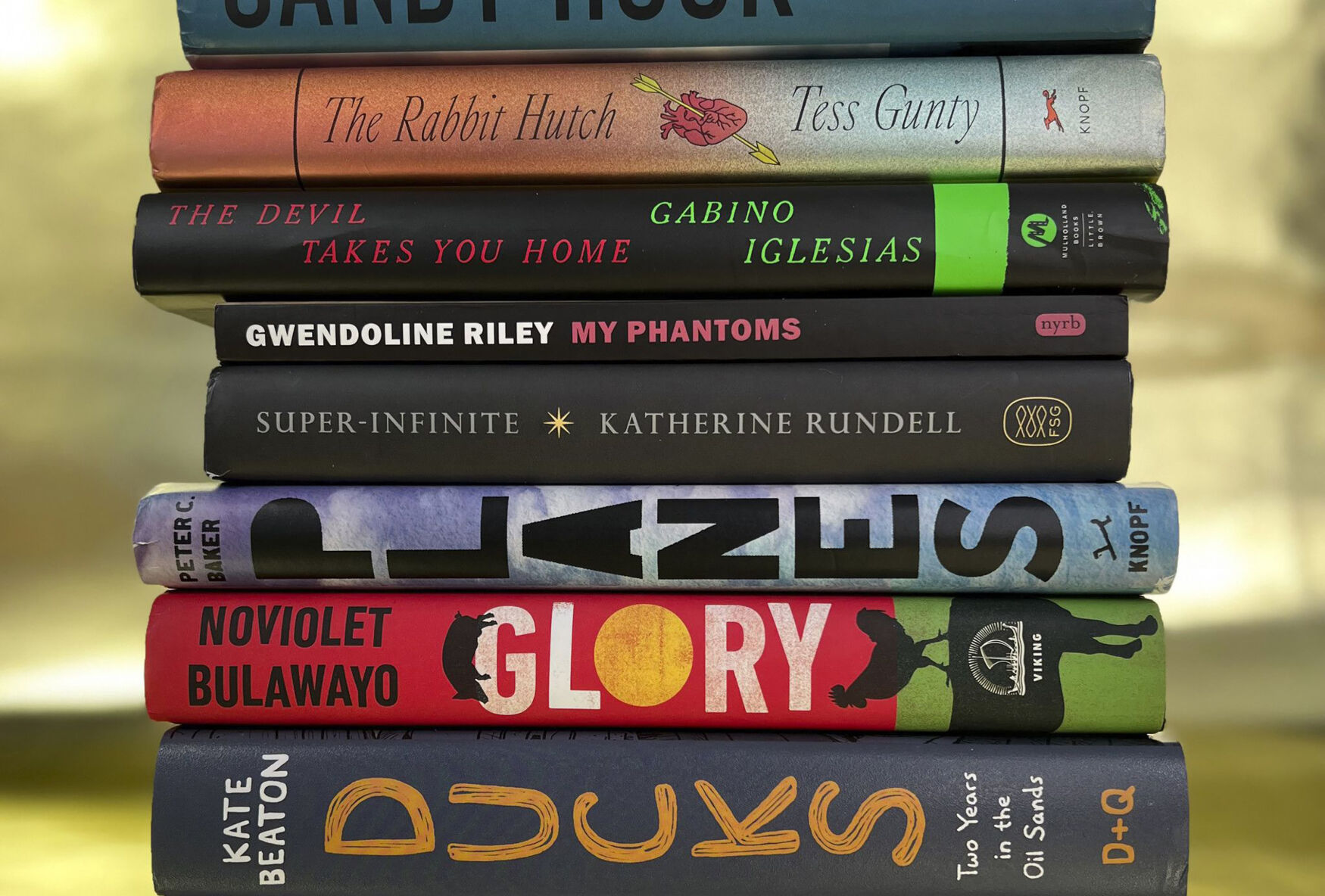

“Planes” (Knopf) by Peter C. Baker: A criminally underrated novel about the ways our choices resonate far beyond ourselves, without our knowledge, in directions we never anticipate. The Evanston, Ill.-based Baker tells compassionate parallel stories: A Muslim woman in Rome pieces together redacted letters from her husband, held in an American black site during the George W. Bush administration; meanwhile, in North Carolina, a real estate agent spars with a conservative school board while having an affair with a businessman who owns a small airline leasing planes to the government for terrorist renditions. Baker does not write victims or villains — just complicated people.

“Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands” (Drawn & Quarterly) by Kate Beaton: A vast graphic memoir about a young cartoonist (Beaton) who leaves her home in Nova Scotia for the supposed gold rush to be found in rural Alberta, where dinosaur-giant machinery carves bleak scars through lush forests. Keaton needs to pay down college loans, but ends up with a street-level view of Canada’s most controversial (and rich) landscape. History rears up, as well as sexual harassment, but also a humane profile of struggling workers, the sorts who produce sneakers, smartphones and fossil fuels but remain faceless.

“Glory” (Viking) by NoViolet Bulawayo: If the premise of this Zimbabwean author’s Booker Prize finalist sounds familiar — an allegorical satire of the ruling class in an African nation, with horses, dogs and goats playing characters clearly inspired by tyrannical former Zimbabwe president Robert Mugabe and others — you’re thinking “Animal Farm.” Yet that costume is worn lightly for this tale of resilience and revolution, documenting the cruelty of the old regime and the performative promises of the new one. The result is an epic that argues with laughter and a lot of anger for the boundlessness of storytelling.

“The Philosophy of Modern Song” (Simon & Schuster) by Bob Dylan: Oh, boy, yup — just what you’d expect from the inscrutable Nobel Prize winner, and nothing you’d expect. To put another way: classic Dylan. And a bit more: A big smile of a read. That academic title is a wink. Dylan selects more than 60 of his favorite songs — nothing more recent than The Clash, many from the 1950s — then leaps into freewheeling history, lots of associative memories and, here and there, thoughts on songwriting and creativity and even a few subjects he has long avoided (such as protest music). It’s also just a joy of smart design, a scrapbook of 20th century America, photos and aesthetics.

“The Rabbit Hutch” (Knopf) by Tess Gunty: Unstable in the very best ways, ambitious without driving you to distraction, touching without sentiment, this snapshot of loneliness in a Midwest apartment block is a transcendent debut. Gunty, a South Bend, Ind., native (and now National Book Award winner for fiction) displays a love of language and rhythm without shortchanging the individuality of every resident. A century after “Winesburg, Ohio,” she updates our American patchwork with spectacular results.

“The Devil Takes You Home” (Mulholland) by Gabino Iglesias: Vintage noir, with an air of “Heart of Darkness,” played at America’s Southern border, for all the racism and heartache that implies. (Iglesias calls it “barrio noir.”) What you’re not expecting is magic realism (and that bit of horror) paired to pitch-dark crime fiction about cyclical violence.

“South to America: A Journey Below the Mason-Dixon to Understand the Soul of a Nation” (Ecco) by Imani Perry: The recent winner of the National Book Award for nonfiction, this is not quite the travelogue that’s promised, but is way more interesting: A genre-trip full of detours into history, folklore, memoir and art, moving state by state, told by a Chicago native determined to push past the archetypes of one region to get at the ways in which the entire country’s legacy of contradictions protects us from hard truths.

“My Phantoms” (New York Review of Books) by Gwendoline Riley: Get on the Riley train. Though unknown in this country, the English writer with a half-dozen short novels to her name has seemed a quiet patron saint of awkward family bonds. Few capture so well the ticklish unease of how adult children relate to difficult parents. Fewer still capture that minefield of everyday conversation. Here, a 40-something academic visits her hermit of a mother, which Riley depicts with a stark, cackle-out-loud precision.

“Super-Infinite: The Transformations of John Donne” (FSG) by Katherine Rundell: What a blast. And how strange to say that about the biography of an Elizabethan poet more associated with unenthusiastic English class assignments than a breezy, bloody, delightful portrait of 17th century England and celebrity. As Rundell — a children’s book author whose premium on clarity is refreshing — writes about Donne: “It’s a little like mounting a horse only to discover that it is an elephant: large and unfamiliar.”

“Sandy Hook: An American Tragedy and the Battle for Truth” (Dutton) by Elizabeth Williamson: At first I read this slowly, almost resistant — the first 50 pages or so is a ground-level, ticktock recounting of the 2012 massacre of New England school children. Your blood pressure spikes. Then Williamson, a New York Times reporter and Beverly native, delivers release: An exacting, moral reckoning for Alex Jones and the online trolls who used the killing as a vehicle to buckle the reality beneath society itself.

Plus 10 more notable books and honorable mentions: “Trust” by Hernan Diaz (Riverhead); “American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis” by Adam Hochschild (Mariner); “Fairy Tale” by Stephen King (Scribner); “What Moves the Dead” by T. Kingfisher (Nightfire); “Art Is Life: Icons & Iconoclasts, Visionaries & Vigilantes, & Flashes of Hope in the Night” by Jerry Saltz (Riverhead); “His Name Is George Floyd: One Man’s Life and the Struggle for Racial Justice” by Robert Samuels and Toluse Olorunnipa (Viking); “Lost & Found” by Kathryn Schulz (Random House); “Camera Man: Buster Keaton, the Dawn of Cinema, and the Invention of the Twentieth Century” by Dana Stevens (Atria); “An Immense World” by Ed Yong (Random House); “Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow” by Gabrielle Zevin (Knopf).

Christopher Borrelli writes for the Chicago Tribune.