Over the course of the last decade, Mike Burgess has been in a prime position to observe the fluctuations in pay in the local manufacturing industry.

Burgess worked as a manager at Collins Aerospace in Bellevue, Iowa, for multiple years. He now serves as the CEO at East Iowa Machine Co. in Farley, Iowa.

At those two positions, he has watched what once was a slow uptick in wages suddenly gain considerable steam.

“I think wages were fairly stable back five years ago,” he said. “In the last three to five years, we’ve seen manufacturing become way more competitive locally. On the entry-level side, companies are no longer paying $10, $11 or $12. Those jobs are paying more like $13, $14 or $15.”

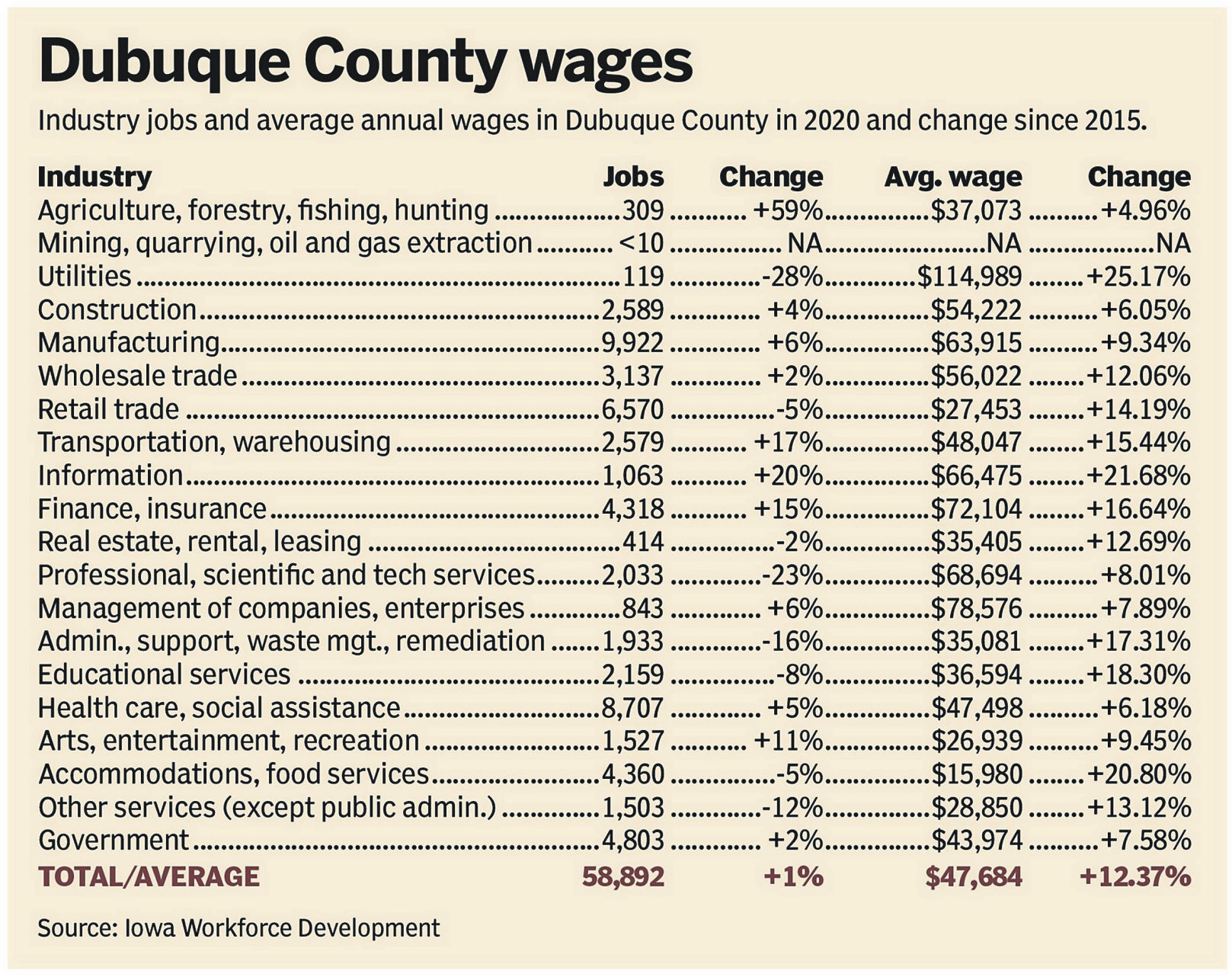

Data maintained by Greater Dubuque Development Corp. shows that average wages for Dubuque County workers in the manufacturing industry rose to $63,915 in 2020, an increase of more than $5,000, or 9.3%, compared to wages from 2015.

And while this uptick seems significant to those in the manufacturing sector, the growth in that industry actually has lagged behind the acceleration of wages in other corners of the economy.

Wages across the county grew by 12.4% in the past half-decade, reaching $47,684 in 2020.

Multiple signs suggest the acceleration of wages is poised to continue.

As growing companies encounter a shallow labor pool, they have been forced to increase pay in order to recruit and retain workers. Local economic experts believe the COVID-19 pandemic — and its further narrowing of the labor market — will merely exacerbate that trend.

Meanwhile, minimum-wage increases in Illinois – and the possibility of similar increases on a federal level — add regulatory pressure to the pay hikes already fueled by free-market forces.

Rick Dickinson, president and CEO of Greater Dubuque Development Corp., believes the figures are evidence that the local economy is headed in the right direction.

He expressed pride in the little things that area leaders have done to propel the economy forward, which has included everything from decreasing the response time in the permitting process to purchasing vast tracts of land that have allowed for industrial growth.

“We have made some significant progress in the last decade,” he said. “Since 2000, with the closure of the packing plant (in 2001), the community really grabbed the regional economy by the horns and made some bold moves to bring it to where we are at today.”

EARNING A REPUTATION

Some industries have shown more signs of growth than others in Dubuque County.

Since 2015, the finance and insurance industry has grown in terms of both jobs and wages, with more than 500 positions added and an increase of 16.6% in wages. That sector now employs 4,318 people with an average wage of $72,104.

Andrew Mozena, president of Premier Bank in Dubuque, said paying higher wages benefits both the bank and its customers.

“There are a lot of costs associated with turnover, and you can avoid those costs by retaining the workforce you have in place,” he said. “On top of that, we have found that customer satisfaction greatly increases where you have a stable group of employees that the customers are dealing with.”

In recent years, Premier Bank has upped the wages for new hires and existing employees.

Mozena wasn’t surprised to see growth in the number of people working in the local finance and insurance industries, either.

Over the years, he believes, Dubuque has established a reputation as a hot spot for those professions. As a result, Mozena has found that graduates from local higher-education institutions — including those who lived outside of the Dubuque area prior to college — have become far more likely to stay in the area as they enter the ranks of the employed.

“Historically, these graduates were going to larger markets, taking jobs in bigger cities like Milwaukee or going out to the East Coast after graduation,” Mozena said. “Most college graduates weren’t seeing the opportunities in Dubuque. Today, people are definitely staying in the area more often.”

In the manufacturing industry, the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic could shape the trajectory of the industry in years to come.

GDDC data shows that the sector added 575 workers from 2015 to 2020, growing the overall employee base in that industry by about 6%.

Burgess, of EIMCo, is unsure whether COVID-19 could dissuade some from entering the industry.

“I believe the pandemic may have turned some people off from manufacturing,” he said. “Some might have developed a fear about working in places that have a lot of people.”

On the other hand, the experience with COVID-19 reinforced the vital role that manufacturing companies must continue to play.

“As an essential business, we kept going strong the entire time,” Burgess said. “We never quit working, and we never stopped needing to hire people.”

LAGGING BEHIND

While the general trajectory of the local economy signals progress, local leaders acknowledge there is still room for improvement.

“Not everyone has benefited from that growth,” Dickinson said. “We shouldn’t confuse improving wages and median household income with universal improvement of the quality of life in the community.”

Those working in the accommodation and food services sector earn an average wage of less than $16,000 per year, despite that figure climbing by about 20% since 2015.

Meanwhile, in the last five years, the retail trade industry has had wages grow by about 14%. Even so, the average worker makes only $27,500.

Rylynn McQuillen, owner of Fig Leaf in downtown Dubuque, emphasized that all retail jobs are not created equal. She believes that her business is just one of many small, locally owned entities that compensates its employees well above the industry average.

“When you are in a corporate atmosphere, sometimes employees can be seen as a replaceable body,” she said. “In your local businesses, they are viewed differently. We realize that these (employees) are the people that customers see when they come in the door. They are a huge part of the experience.”

McQuillen noted that small boutiques have gained momentum in recent years and said that likely propped up wages in the last half-decade and could contribute to higher earnings in the years ahead.

She hopes the general momentum of smaller boutiques, coupled with the raises she gives her own workers, will send the message that the job could be a long-term fit.

“Some people may think (of retail) as a job they can fall back on,” she said. “We want them to see it as a job they can grow into.”

In some industries, wages lag behind the area average despite requiring high levels of education.

Wages for those in the educational services category increased by more than 18% in the last five years, raising the average wage to about $36,600. Despite the recent increase, this lags considerably behind the overall county wage average.

Amy Hawkins, the chief human resources officer for Dubuque Community Schools, acknowledged that those entering the field of education aren’t doing so to strike it rich.

“People who go into education have a passion for kids and a passion for giving back to the community,” she said.

She noted that two primary factors — longevity and obtaining higher levels of education, most notably a master’s degree — can bump up a teacher’s wage.

Unlike many other industries, where free-market forces largely determine wage changes, local school districts are consistently influenced by the decisions of elected leaders.

Hawkins noted that state lawmakers largely determine the extent to which school districts can increase their budget in a particular year.

Iowa legislators once routinely approved state supplemental aid increases of 4%. More recently, that figure has fallen lower.

“I was surprised to see the wages (for educators) grew as much as they did in the last five years,” Hawkins said.

MULTIPLE VARIABLES

In northwest Illinois, a pair of phenomena are providing upward pressure on wages, according to Executive Director Emily Legel, of Northwest Illinois Economic Development.

First, mirroring trends in northeast Iowa, the scarcity of available workforce has ushered in an era of competition among employers. This forced businesses to pay more to attract and retain workers, explained Legel.

More recently, regulatory pressure has provided its own upward pressure on wages.

Gov. J.B. Pritzker in 2019 signed a bill that will raise the minimum wage from $8.25 per hour to $15 per hour in 2025 via a series of smaller increases. The first three steps in the plan have taken effect, the most recent of which pushed required hourly pay to $11.

Legel said the climbing minimum wage has “raised the floor” in a handful of industries that traditionally paid poorly.

Utilizing an admittedly unscientific form of analysis, Legel said she already has seen evidence that the rising minimum wage is bringing new workers into Galena.

“At employers like McDonald’s and Walmart, it is clear that some people are already coming across the border,” she said. “You can see the license plates from other states.”

But the mandated wage hikes also could have the opposite impact, driving companies out of the region that cannot keep pace with the required increases.

“I think we will see some employers leave who cannot keep up with it,” she said.

In southwest Wisconsin, many of the trends observed in northeast Iowa hold true.

Ron Brisbois, executive director of Grant County Economic Development Corp., said his organization does not have updated wage data showing trends for specific industries in the county.

But he has noticed significant growth in the manufacturing sector in the last half-decade.

“It is one of the largest increases to blue-collar wages I have seen in some time,” Brisbois said.

The growth in these jobs has effectively “closed the gap” between blue- and white-collar positions.

These wage trends — coupled with a concerted effort to change the perception surrounding blue-collar work and making those jobs more palatable to young adults — could lead to continued growth in the number of manufacturing workers, Brisbois predicted.

He believes that the health care field also is poised for consistent growth in years to come. This is largely due to demographics, with an increasingly older population driving the need for medical care.

“I have noticed a significant increase, and I think that will continue to be a high-demand area,” he said. “The number of elderly and retirement-age people is rising and will continue to rise.”

WHAT LIES AHEAD?

While the data provided by GDDC provides a snapshot of wages in 2020, Dickinson said such figures likely don’t factor in the full impact of the pandemic.

COVID-19 touched virtually every corner of the economy in 2020, creating abrupt, industrywide shutdowns in the spring and leaving a permanent mark on other sectors of the economy even as the calendar turned to 2021.

In the spring, when many businesses were under mandated shutdowns, unemployment in Dubuque County peaked at 20%.

Dickinson thinks the pandemic will result in the emergence of two, seemingly contradictory trends.

“I think enough people lost their jobs or chose to leave the workforce during the pandemic that it will result in a decrease in median household income,” he said. “In terms of the average wage, though, I think you will actually see that go up because (COVID-19) put even more pressure on the available workforce.”

A recent shift in America’s political landscape also could reverberate across the local economy.

Ahead of his inauguration, President Joe Biden expressed a desire to gradually raise the federal minimum wage from its current rate of $7.25 per hour to $15.

If passed, that legislation would more than double the minimum wage in states that still adhere to the federal rate, including Iowa and Wisconsin.

Brisbois, of Grant County (Wis.) Economic Development Corp., said a mandate to increase wages could alter local companies’ approach to growth, particularly in the manufacturing industry.

“Manufacturers are trying to grow, and there are a couple of different ways they can do that,” he said. “Local companies are looking to add and retain workers, and they are also turning to automation to increase product. If they are not able to find bodies or if it becomes much more expensive to add those workers, they could look even more to automation.”

Amid the economic struggles wrought by the pandemic, the past year came to a close with a major, positive economic development announcement.

Simmons Pet Food in December announced plans to invest $80 million in a manufacturing facility in Dubuque and create 270 full-time jobs.

Documents submitted to state officials indicated that the average hourly starting wage for these employees will be $22.18.

In December, Dickinson proclaimed that the presence of Simmons Pet Food would “raise the bar” and put pressure on local businesses to increase wages.

Such upward pressure would create more options for employees and potentially complicate the efforts of local businesses looking to add workers.

Burgess, who has worked closely with the GDDC in addition to leading EIMCo, believes the arrival of the new company is more positive news for an economy that has largely remained strong in spite of recent economic hardships.

“The goal is not only to bring more jobs but also to create the kinds of opportunities that entice new people to come to the community,” he said.