I’ve been reading about working from home.

Because I’ve been working from home. I’m writing this from home. Not coincidentally, I’m also reading about that thing none of us were supposed to feel once we embraced working from home. I’m reading about burnout, its history, its costs.

To be specific, I’ve been reading books about working from home and burnout early in the morning, before dawn, which is how I read a lot of books these days, before anyone is awake and the demands of work and life creep in to gunk up everything.

Except, of course, if I’m real honest: The dividing line between work and life is no longer a balance but an avalanche zone. That reading part is now the work part, and the work part is also the life part, and so, in short: I am working from home and usually, burned out. As is the guy editing this.

As are you.

I should feel refreshed by a holiday break. Instead, I’m wondering, once more: Do I work enough? Do I work too much? Should I answer this email at 10:30 at night? What’s that pain in my right side? Is there something wrong with my left ear? Why is child care so expensive? How soon before I’m living in my car?

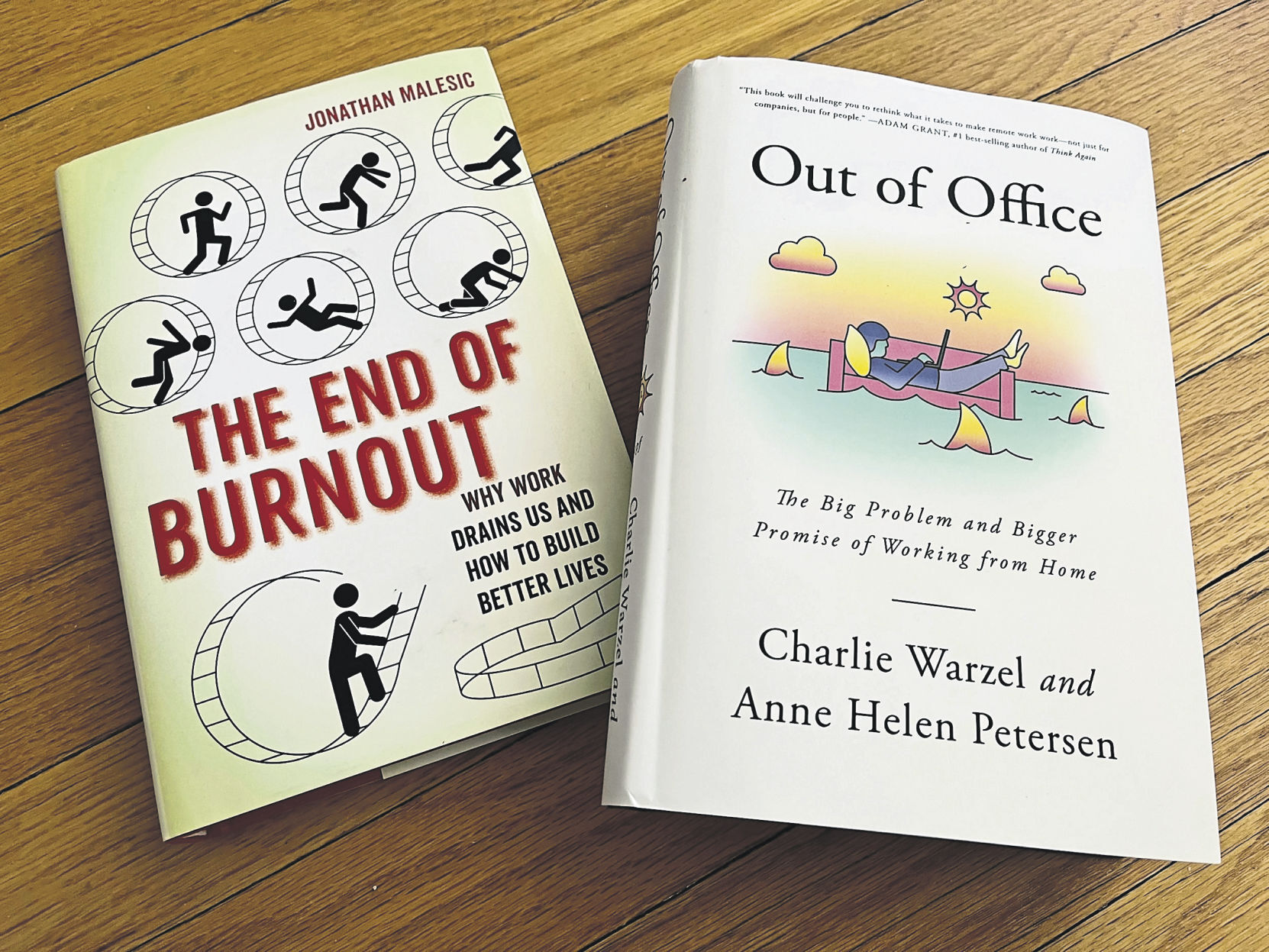

The irony of reading Jonathan Malesic’s “The End of Burnout: Why Work Drains Us and How to Build Better Lives” (University of California Press, $28) and Charlie Warzel and Anne Helen Petersen’s “Out of Office: The Big Problem and Bigger Promise of Working From Home” (Knopf, $27) — both of which resemble inspirational business self-help but are rousing arguments against the way we work now — is they stressed me the hell out.

The way any bit of wise, difficult advice should stress you out:

Now that you know what you must do, you must act.

Assuming you find the time.

“The End of Burnout” is the more invigorating of these books, a reimagining of how we think of the fabled “dignity of work” and Plato’s “noble li,” of head-down, no-complaining labor as a primary “source of dignity, character and purpose.”

Among its finest moments is a reading of “Walden” that plays down solitude to consider, in a sense, Thoreau’s quiet case for staying sane and gainfully employed. But then Malesic recognizes the trouble of walking that walk, of developing the kind of self-determination necessary to assume your time does not belong to your employer. Not even Kanye — who famously rapped “Let’s have a toast for the (expletives)/That’ll never take work off” — slows down.

Written with the lively, lived-in confidence of a good journalist, it’s surprisingly fun, and a smart compliment to “Out of Office,” which itself reads like a necessary, of-the moment dispatch from our overworked brains, still processing the past couple of years, struggling to make sense of an office away from the office, wondering if you’re the only one who feels nuts.

You’re not. Have you seen the latest jobs report? More of us have chosen not to return to business as usual. The New York Times reported that even low-level grunts are becoming increasingly bold about telling off their lousy bosses. Our mass take-your-job-and-shove-it has even acquired a well-known moniker, the Great Resignation.

Pandemic or not, read “Out of Office” and realize: It was all bound to happen.

Warzel and Petersen are particularly good on the Orwellian language that chips away at good will. They don’t knock companies that call their employees “family” — a business should aspire to a loving, supportive culture — but “you already have a family … and when a company uses that rhetoric, it is reframing a transactional relationship as an emotional one.”

They devote a full chapter to the grand joke of “flextime” and hallowed “flexible” work environments, and though there’s nothing here many of us don’t know — “If a company doesn’t have enough employees to absorb the labor of someone taking time off … you’ll end up in a stew of resentment and overwork” — it’s nice to see it spelled out, as well as given a history, real-world examples, even future scenarios.

All of which are the real strengths of “Out of Office.” As with “End of Burnout,” written by a journalist more interested in ideas than business book manifestos, “Out of Office” is the work of journalists who specialize in culture, not optimizing, pivoting or thinking out of the box.

They don’t dwell on best practices, scale upward, circle back or drill down.

They pull them apart. They don’t seek easy solutions to the evolving work-at-home conundrum, but dig into experiments, studies and interviews, highlighting promise and problems in equal measure. There’s evidence that working from home has been a boon for Black women, that studies have found they flourish outside of workplaces where they “often grappled with internalized pressure to groom and conduct themselves as exemplars.” On the other hand, there’s worries of surveillance, a lack of community.

I’m not a fan of business books.

They hold a prominent, annoying place on airport bookshelves, their covers pale and impenetrable, their titles interchangeable and prescriptive; back in the days of traveling daily into downtown Chicago with the CTA, these books were so dog-eared and underlined beneath arms of fellow commuters, I sometimes wondered if they were reading treatises on productivity or how to win friends and influence people in a cult.

“Out of Office” and “The End of Burnout” are not business books in that sense, but you can tell their authors suffered those books, along with books on the decline of once-confidence businesses. Hubris and history, among workers and bosses alike, receive context here, again and again. The ‘50s Organization Man, who lived in the office, was “lulled by paternalistic companies, only to be betrayed by them the moment times got tough.” Malesic notes early cries of burnout, in the work by Graham Greene, Bob Dylan.

None of this is new.

It’s just closer now, on your iPhone, feet from your bed. Do more with less. Lose yourself in work. Drink plenty of fluids. Take that flextime. Limit yourself to one bagel.

They’re not free.

Christopher Borrelli writes for the Chicago Tribune.