KYIV, Ukraine (AP) — Ukraine’s leaders sought Tuesday to reassure the nation that an invasion from neighboring Russia was not imminent, even as they acknowledged the threat is real and received a shipment of U.S. military equipment to shore up their defenses.

Moscow has denied it is planning an assault, but it has massed an estimated 100,000 troops near Ukraine in recent weeks and is holding military drills at multiple locations in Russia. That has led the United States and its NATO allies to rush to prepare for a possible war.

U.S. President Joe Biden told reporters that Russian President Vladimir Putin “continues to build forces along Ukraine’s border,” and an attack “would be the largest invasion since World War II. It would change the world.”

Several rounds of high stakes diplomacy have failed to yield any breakthroughs, and tensions escalated further this week. NATO said it was bolstering its deterrence in the Baltic Sea region, and the U.S. ordered 8,500 troops on higher alert for potential deployment to Europe as part of an alliance “response force” if necessary. British Prime Minister Boris Johnson also said he is prepared to send troops to protect NATO allies in Europe.

“We have no intention of putting American forces or NATO forces in Ukraine,” Biden said, adding that there would be serious economic consequences for Putin, including personal sanctions, in the event of an invasion.

In a show of European unity in Berlin, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and French President Emmanuel Macron called for an easing of the crisis.

Scholz said he wanted “clear steps from Russia that will contribute to a de-escalation of the situation.” Macron, who said he would talk to Putin by phone Friday, added: “If there is aggression, there will be retaliation and the cost will be very high.”

The U.S. and its allies have threatened sanctions like never before if Moscow sends its military into Ukraine, but they have given few details, saying it’s best to keep Putin guessing.

The U.S. State Department has ordered the families of all American personnel at the U.S. Embassy in Kyiv to leave the country, and it said that nonessential embassy staff could leave. Britain said it, too, was withdrawing some diplomats and dependents from its embassy, and families of Canadian diplomatic staff also have been told to leave.

Ukrainian authorities, however, have sought to project calm. Speaking in the second televised speech to the nation in as many days, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy urged Ukrainians not to panic.

“We are strong enough to keep everything under control and derail any attempts at destabilization,” he said.

The decision by the U.S., Britain, Australia, Germany and Canada to withdraw some of their diplomats and dependents from Kyiv “doesn’t necessarily signal an inevitable escalation and is part of a complex diplomatic game,” he said. ”We are working together with our partners as a single team.”

Defense Minister Oleksii Reznikov told parliament that “as of today, there are no grounds to believe” Russia will invade imminently, noting that its troops have not formed what he called a battle group to force its way over the border.

“Don’t worry, sleep well,” he said. “No need to have your bags packed.”

In an interview late Monday, however, he acknowledged “risky scenarios” are possible.

Russia has said Western accusations it is planning an attack are merely a cover for NATO’s own planned provocations. Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov again accused the U.S. of “fomenting tensions” around Ukraine, a former Soviet state that has been in a conflict with Russia for almost eight years.

Moscow has rejected Western demands to pull its troops back from areas near Ukraine, saying it will deploy and train them wherever necessary on its territory as a response to what it called “hostile” moves by the U.S. and its allies. Thousands of troops from Russia’s Southern and Western Military Districts took part Tuesday in readiness drills in those regions in maneuvers involving Iskander missiles and dozens of warplanes.

In 2014, following the ouster of a Kremlin-friendly president in Kyiv, Moscow annexed Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula and threw its weight behind a separatist insurgency in the country’s eastern industrial heartland. Fighting between Ukrainian forces and Russia-backed rebels has killed over 14,000 people, and efforts to reach a settlement have stalled.

In the latest standoff, Russia wants guarantees from the West that NATO will never admit Ukraine as a member and that the alliance would curtail other actions, such as stationing troops in former Soviet bloc countries. Some of these, like the membership pledge, are nonstarters for NATO, creating a seemingly intractable stalemate that many fear can only end in a war.

Moscow has accused Ukraine of massing troops near rebel-controlled regions to retake them by force — accusations Kyiv has rejected.

Analysts say Ukraine’s leaders are caught between trying to calm the nation and ensuring it gets sufficient assistance from the West in case of an invasion.

“The Kremlin’s plans include undermining the situation inside Ukraine, fomenting hysteria and fear among Ukrainians, and the authorities in Kyiv find it increasingly difficult to contain this snowball,” said political analyst Volodymyr Fesenko.

Kyiv resident Andrey Chekonovsky said Ukrainians have been living with the threat of a Russian attack for eight years, “and I think that the fact that we are worried now is connected with diplomatic games.”

The crisis didn’t stop a large group of people from rallying outside parliament, demanding changes to the country’s tax regulations and even clashing with police at one point.

Other Ukrainians are watching warily.

“Of course we fear Russia’s aggression and a war, which will lead to the further impoverishment of Ukrainians. But we will be forced to fight and defend ourselves,” said Dmytro Ugol, a 46-year-old construction worker in Kyiv. “I am prepared to fight, but my entire family doesn’t want it and lives in tension. Every day, the news scares us more and more.”

Putting U.S.-based troops on heightened alert for Europe on Monday suggested diminishing hope in the West that Putin will back away.

The Pentagon said Tuesday it is still identifying the roughly 8,500 U.S. troops being placed on higher alert for possible deployment to Europe, and said that more could be tapped if needed. The U.S. is still in “active consultation” with allies about the capabilities they might need, said press secretary John Kirby.

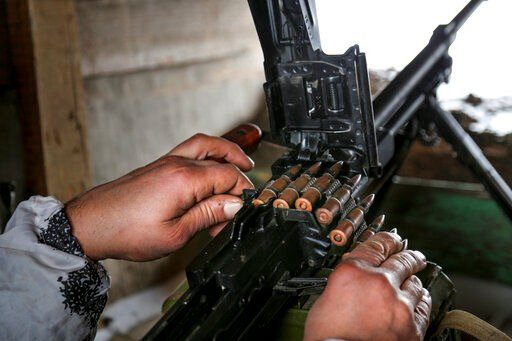

As part of a new $200 million in security assistance directed to Ukraine from the United States, a shipment including equipment and munitions arrived Tuesday in Ukraine, according to Deputy Defense Minister Hanna Maliar.

If Russia invades, “we will provide additional defensive material to the Ukrainians, above and beyond what we have already sent,” U.S. Chargé d’Affaires in Ukraine Kristina Kvien said at the airport.

“And let me underscore that Russian soldiers sent to Ukraine at the behest of the Kremlin will face fierce resistance. The losses to Russia will be heavy,” Kvien said.

The U.S. moves are being coordinated with other NATO members to bolster a defensive presence in Eastern Europe. Denmark is sending a frigate and F-16 warplanes to Lithuania; Spain is sending four fighter jets to Bulgaria and three ships to the Black Sea to join NATO naval forces, and France stands ready to send troops to Romania.

Biden’s national security team has been working with several European nations, the European Commission, and global suppliers on contingency plans if Russia cuts off energy, according to two senior administration officials who briefed reporters about efforts to mitigate spillover effects from potential military action. The officials spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss the deliberations.

If needed, Europe would look to natural gas supplies in North Africa, the Middle East, Asia and the U.S. The effort would require “rather smaller volumes from a multitude of sources” to make up for a Russian cutoff, according to one official.

—-

Ellen Knickmeyer, Lolita Baldor and Aamer Madhani in Washington, Dasha Litvinova and Vladimir Isachenkov in Moscow, Kirsten Grieshaber in Berlin, Barbara Surk in Nice, France, and Sylvia Hui in London contributed.