Despite continuing to boast low unemployment rates, local Iowa counties have observed major declines in their labor force over the course of the past 12 months.

Data released by Iowa Workforce Development last week showed an unemployment rate of just 3.5% in Dubuque County, well below the national jobless rate of 6.7% and only a tick above the December 2019 rate of 3.1%.

A closer look at underlying data, however, reveals seismic shifts in the makeup of the workforce.

State data shows that 55,500 Dubuque County residents were employed in December 2019. One year later, in December 2020, that figure had fallen by 5,000, or about 9% .

Rick Dickinson, president and CEO of Greater Dubuque Development Corp., believes that 5,000-job decline is, by far, a more telling indicator than the low unemployment rate.

“We as a community need to turn our eyes away from (the unemployment rate) and look at the facts beneath it so we can understand the challenges we face,” he said. “There are a number of individuals struggling in this pandemic.”

Dubuque County’s decline in employment wasn’t unique to the region.

Clayton, Delaware, Jackson and Jones counties also boasted unemployment rates in December that were below the national average and comparable to the jobless rates reported one year prior. Despite these figures, the actual number of individuals employed dropped dramatically.

In Jackson County, for instance, the state reported employment of 10,820 in December 2019. By the final month of 2020, employment had declined to 9,880 — an about 9% decrease.

Clayton, Delaware and Jones counties also saw precipitous declines in employment but not unemployment rate.

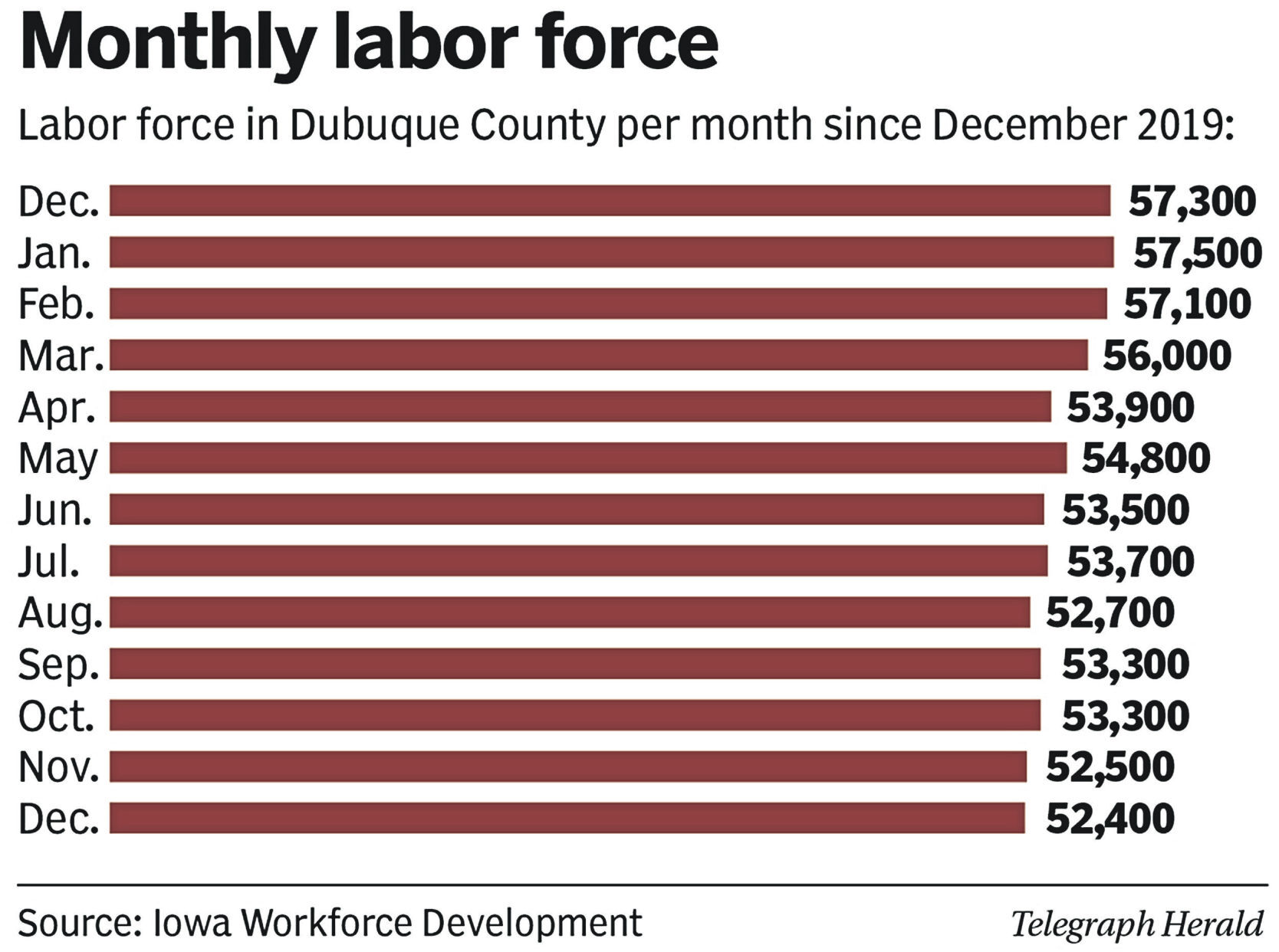

In each of these counties, the jobless rate remained stable because the labor force — a measure of all people who are currently working or actively seeking employment — cratered in the past year. In other words, many out-of-work residents didn’t factor into the unemployment rate because they had exited the labor force and given up on looking for a position altogether.

Nicolas Hockenberry, director of Jackson County Economic Alliance, said this trend was fueled in part by the pandemic’s influence on education.

“When schools shut down, it put a lot of pressure on two-worker households to find a solution for child care,” he said. “Their options were either paying someone for that child care or having one of the parents stay home with the kids.”

Hockenberry said many couples chose the latter scenario, resulting in a sudden and significant decline in the number of parents in the workforce.

It remains to be seen whether this phenomenon will permanently alter workforce dynamics. But Hockenberry suspects that some lasting impact will occur.

“If that scenario worked for them, they will be less likely to return to the workforce (post-pandemic),” Hockenberry said. “People have a way of adjusting to the new normal.”

The significant decline in the local labor force comes at a time when companies are desperately seeking to fill vacant positions.

Dickinson noted that the website AccessDubuqueJobs.com currently shows about 1,600 jobs available in the region. For the well-being of the local economy, he emphasized that it is critical to pair those who aren’t working with those open jobs.

However, Dickinson expressed concern that the very services meant to accomplish that goal have eroded over the last two decades.

Organizations like the Department of Human Services and Iowa Workforce Development have shuttered many of their offices across the state and turned to more virtual options. In the process, they have lost much of the human element that allows professionals to pair job-seekers with a job that fits their skills and needs.

This trend has left much of the state flat-footed in the face of the current economic crisis, according to Dickinson.

“We have been dealing with this unique circumstance (caused by the pandemic), and we are not in a very good spot to react to it,” Dickinson said.