DALLAS — It was the start of a steamy Friday two Augusts ago when Jason Whisler settled in for a working breakfast at the Coffee Ranch restaurant in the Texas Panhandle city of Borger. The most pressing agenda item for city officials that morning: planning for a country music concert and anniversary event.

Then Whisler’s phone rang. Borger’s computer system had been hacked.

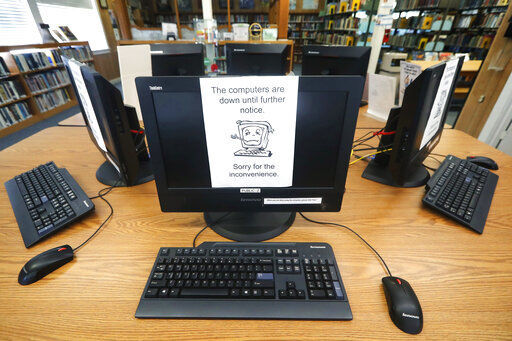

Workers were frozen out of files. Printers spewed out demands for money. Over the next several days, residents couldn’t pay water bills, the government couldn’t process payroll, police officers couldn’t retrieve certain records. Across Texas, similar scenes played out in nearly two dozen communities hit by a cyberattack officials ultimately tied to a Russia-based criminal syndicate.

In 2019, ransomware had yet to emerge as one of the top national security concerns confronting the United States, an issue that would become the focus of a presidential summit between Washington and Moscow this year. But the attacks in Texas were a harbinger of the now-exploding threat and offer a vivid case study in what happens behind the scenes when small-town America comes under attack.

Texas communities struggled for days with disruptions to core government services as workers in small cities and towns endured a cascade of frustrations brought on by the sophisticated cyberattack, according to thousands of pages of documents reviewed by The Associated Press and interviews with people involved in the response. The AP also learned new details about the attack’s scope and victims, including an Air Force base where access to a law enforcement database was interrupted, and a city forced to operate its water-supply system manually.

In recent months, a ransomware attack led to gasoline shortages. Another, tied to the same hacking gang that attacked the Texas communities, threatened meat supplies. But the Texas attacks — which, unlike these prominent cases, were resolved without a ransom payment — make clear that ransomware need not hit vital infrastructure or major corporations to interrupt daily life.

“It was just a scary feeling,” Whisler, Borger’s emergency management coordinator, recounted in an interview.

In the early morning of Aug. 16, as most Texans were still asleep, hackers half a world away were burrowing into networks. They encrypted files and left ransom notes.

That afternoon, with the attack’s impact becoming apparent, the city manager of Vernon emailed colleagues about a “ransom type” virus affecting the police department. The city near the Oklahoma state line could get back online by paying the $2.5 million the hackers were demanding, he wrote, but that was “obviously” not the plan.

“Holy moly!!!!!” replied city commissioner Pam Gosline, now the mayor.

The culprits were affiliated with REvil, the Russia-linked syndicate that last spring extorted $11 million from meat-processor JBS and more recently was behind a Fourth of July weekend attack that crippled businesses around the globe. In the Texas case, however, communities were ultimately able to recover most of their data and rebuild their systems without anyone paying ransom.

The hackers gained their foothold through an attack on a Texas firm that provides technology services to local governments, branching through screen-sharing software and remote administration to seize control of the networks of some of the company’s clients.

An early hint of trouble came with a 2 a.m. phone call to the firm’s president, Richard Myers. His company, TSM Consulting Services Inc., provides data communications service for Texas communities, linking police agencies to a statewide law enforcement database.

One of his client’s servers was unresponsive, he was told. Upon inspection, Myers noticed that someone who wasn’t supposed to be in the computer system was trying to install something remotely. He rebooted the server. Things initially seemed fixed until the department called back: One of its laptops had a ransom note on it.

It soon became clear the problem wasn’t isolated to a single client.

“I don’t think you can begin to express the terror that goes through your mind when something like that starts to unfold,” he said.

Within hours, state officials were hunkered inside an underground operations center normally used for calamities like hurricanes and floods. Gov. Greg Abbott declared it a cyber disaster. Texas National Guard cyber specialists were activated.

“If you needed to build something — you needed an inspection, something like that — out of luck for a week,” said Andy Bennett, the state’s then-deputy chief information security officer. “Records look-ups? Couldn’t go look up records. Basically, if there’s a municipal function that you would go down to a city hall for, or that you would rely on the police department for, it wasn’t available.”

In Borger, a city of fewer than 13,000, early indications were worrisome as the city raced to shut down its computers.

Gibberish ransom demands spat out of printers and displayed on some computer screens. Government files were encrypted, with titles like “Budget Document” replaced by nonsensical combinations of letters and symbols, said current city manager Garrett Spradling.

Vital records, like birth and death certificates, were offline. Payments couldn’t be processed, checks couldn’t be issued — though, blessedly for Borger, it was an off-week for payroll. Signs posted on a drive-up window outside City Hall told residents the city couldn’t process water bill payments but cutoffs would be delayed.

One update shared with city officials soon after the attack described how every server was infected, as were about 60% of the 85 computers inspected by that point. A city government email told council members that agendas for a meeting would be in paper format, “since your tablets won’t be able to connect.” An official told a judge it was unclear if computer systems would be operational in time for trials two days away.

Because the city had paid for offsite remote backup, Borger had the capability to reformat servers, reinstall the operating system and bring data back over. A newly purchased server that had yet to be installed came in handy. The police department, however, retained its data locally and the attack hampered officers’ access to previous incident reports, Spradling said.

As they worked to resolve the problem, officials shared draft press releases that offered reassurances that critical emergency operations would continue and that the attacks weren’t a reflection of any misstep by the city.

One councilmember, a military veteran named Milton Ooley, cautioned against publicity for the hackers’ “form of terrorism.”

“This is consistent with my firsthand experience with how the U.S. handled terrorism in Europe when I was there in the late ’70s, some of which was directed at U.S. units including missile units I worked with/in during those days,” he wrote colleagues. In an interview, he said he believed the public was entitled to information but hackers didn’t deserve notoriety.

The day of the attack, Jeremy Sereno was working his civilian job at Dell when he was contacted by the state about the attack. A lieutenant colonel and senior cybersecurity officer with the Texas Military Department, Sereno began helping deploy Texas National Guard troops to hacked cities, where specialists over the next two weeks helped assess the damage, restore data from backed-up files and retake control of locked systems.

One of the first areas of concern was a small North Texas city where the attack locked the “human-machine interface” that workers used to control the water supply, forcing them to operate the system manually, Sereno said. Water purity was not endangered.

“That was probably our biggest number one,” Sereno said. “That’s what’s considered critical infrastructure, when you talk about water.”

AP is not identifying the city at the urging of state officials, who said doing so could draw new attacks on its water system.

In Graham, a small city a couple of hours west of Dallas, the computer virus attacked a police server housing body-camera videos, causing hundreds of them to be lost, said Sgt. Chris Denney.

For days, officers had to use notebooks and pens to take reports. Instead of using mobile data terminals to run checks on people, officers had to rely on requests to dispatchers of a sheriff’s office that was unaffected by the attack, said Chief Brent Bullock.

“That’s been at these officers’ fingertips for years, and then all of a sudden, they don’t have that anymore,” Bullock said. Officers, he added, “kind of had to go back to old school.”

Other communities preemptively took potentially vulnerable systems offline. In the Austin suburb of Leander, the city shut off the program that police used to check license plates for 24 hours as IT staff worked to confirm that it hadn’t been exposed.

Emails reveal moments of exasperation as problems persisted.

Spradling complained to an outside technology company about “massive delays” in getting a response to a support request. Local technology managers griped about what they perceived as state and law enforcement secretiveness. Several in cities that were not hit complained in emails after the attack that they hadn’t been told what company the ransomware spread from and didn’t have enough information to ensure their systems were safe.

The impact wasn’t limited to local governments. Sheppard Air Force Base confirmed to AP that its access to a statewide law enforcement database used for background checks on visitors was temporarily interrupted, causing delays for issuing passes. Operations were otherwise unaffected.

Officials at Joint Base San Antonio Randolph, which public records indicated was also affected, did not directly answer questions about the hack but said that it had no impact on “missions or network security” and the base “as a whole” was not a target.

One complication: TSM’s customer list was itself encrypted, though eventually a copy was procured, officials said. State officials didn’t immediately know which communities had been victimized. They called around asking, “Were you impacted? Were you impacted? Were you impacted?” said Nancy Rainosek, Texas’ chief information security officer.

“There was one place that we contacted and they said, ‘no, no, we’re not hit,’” Rainosek said. Then, days later, “they said, ‘yes, we were.’”

State officials spent a full week inside their command post — built to withstand a nuclear blast — and used a map to chart the attack’s spread. All told, some 23 government entities were ultimately shaded to indicate they’d been hit.

“It’s a bit of a mind struggle because you’re trying to stay focused and present on the folks that you know about,” said Amanda Crawford, executive director of the Texas Information Resources Department. “But you’re continually worrying about, ‘Is there something you’re missing? Or are there others, that you’re going to get another call that somebody else has been hit?’”

By Wednesday evening, records show, most city services in Borger were restored, including utility payments, vital statistics and most employee computers. The situation had stabilized; the city ended up with about 80% of its data back and the concert Whisler was planning happened as scheduled.

Still, in a city with a roughly $31 million budget, Borger had overtime IT expenses to contend with and purchased $44,000 worth of new computers. It’s invested in additional cybersecurity protections, including some $30,000 in annual costs for additional remote backup.

Borger officials in the weeks before the hack had discussed upgrading the threat level from cyberattacks. Those considerations are now more than theoretical.

“When you complain about having to change your passwords, you complain a lot more when it’s never happened to you and you don’t have anything to relate it to,” Spradling said. “You tend to complain a little less after you’ve had to answer the phone and tell 300 people they couldn’t pay their water bill.”

But damage remains two years later.

Sometimes even now, Spradling said, officials will go to pull an old report or address record — only to find it isn’t there.