LONDON — The U.K. indicated Tuesday that it was prepared to break an international agreement as post-Brexit trade discussions with the European Union resumed on an increasingly acrimonious tone.

With concerns mounting that the talks could be just weeks from collapse, the U.K. urged the EU to show “more realism” in the discussions, while the 27-nation bloc noted that it was a “world power” that would stand its ground and not yield to threats.

The latest round of discussions kicked off in London in an air of pessimism because of concerns that the British government is prepared to violate international law by reneging on commitments made before the country’s departure from the bloc on Jan. 31.

Northern Ireland Secretary Brandon Lewis appeared to admit as much when he told lawmakers that legislation to be published Wednesday would change aspects of the Brexit withdrawal agreement between the U.K. and the EU.

Though details of the Internal Market Bill are unclear, Lewis said the planned legislation as it relates to Northern Ireland “does break international law in a very specific and limited way.”

EU officials have said any attempt to override the international treaty could jeopardize peace in Northern Ireland as well as undermine the chances of any trade deal. Under the terms of Britain’s departure, the government has committed itself to ensuring an open border between Northern Ireland, which is part of the U.K., and EU member Ireland.

“We fully expect the UK to honor the commitments that it negotiated and signed up to,” said EU Parliament President David Sassoli. “Any attempts by the UK to undermine the agreement would have serious consequences,” he said after meeting EU chief negotiator Michel Barnier.

Johnson’s predecessor, Theresa May, raised concerns that any attempt to bypass commitments could damage the U.K.’s international standing.

“How can the government reassure future international partners that the U.K. can be trusted to abide by the legal obligations of the agreements it signs?” she said in the House of Commons.

The news that the head of the British government’s legal department, Jonathan Jones, quit — reportedly over plans to bypass commitments made with regard to the Irish border — only added to the sense the talks are going nowhere.

Though the U.K. left the bloc on Jan. 31, it is in a transition period that effectively sees it abide by EU rules until the end of this year. The discussions are about agreeing to the broad outlines of the trading relationship from the start of 2021.

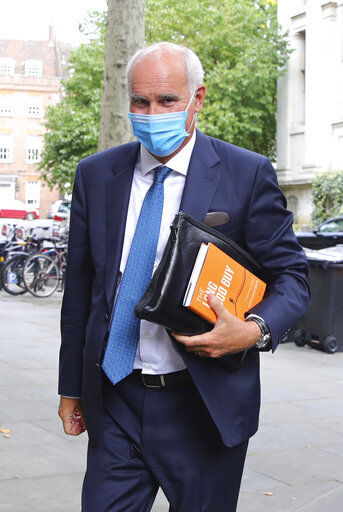

David Frost, the British government’s chief negotiator, said the two sides “can no longer afford to go over well-trodden ground” and that the EU needs to show “more realism” about the U.K.’s status as an independent country.

European Council President Charles Michel retorted that the bloc is in no mood to budge on its demands.

“We are sending a message, not only to our citizens but also to the rest of the world — Europe is a world power and we are ready to defend our interests,” he said in a speech Tuesday at the Brussels Economic Forum.

The trade discussions have made very little progress over the summer, with the two sides seemingly wide apart on several issues, notably on business regulations, the extent to which the U.K. can support certain industries and over the EU fishing fleet’s access to British waters.

The EU has been particularly insistent on level playing field issues in order to ensure that British-based businesses don’t have an unfair advantage as a result of laxer social, environmental or subsidy rules in the U.K.

“If foreign companies want access to our market, we expect them to be on the same footing as our European companies,” Michel said.

The British government has said the publication of planned legislation on Wednesday is intended to tie up some “loose ends” where there was a need for “legal certainty.”

Johnson has said Britain could walk away from the talks within weeks and insists that a no-deal exit would be a “good outcome for the U.K.” He said in a statement that any agreement must be sealed by an EU summit scheduled for Oct. 15.

British businesses are worried about a collapse in the talks that could see tariffs and other impediments slapped on trade with the EU at the start of next year. Most economists think that the costs of a “no-deal” outcome would fall disproportionately on the U.K.

———

Raf Casert reported from Brussels.

———

Follow all AP stories about Brexit and British politics at https://apnews.com/Brexit