Recalling his years behind bars recently, the actor Danny Trejo sometimes snorted or rubbed his face with both hands, as if bracing himself against traumas a half-century old.

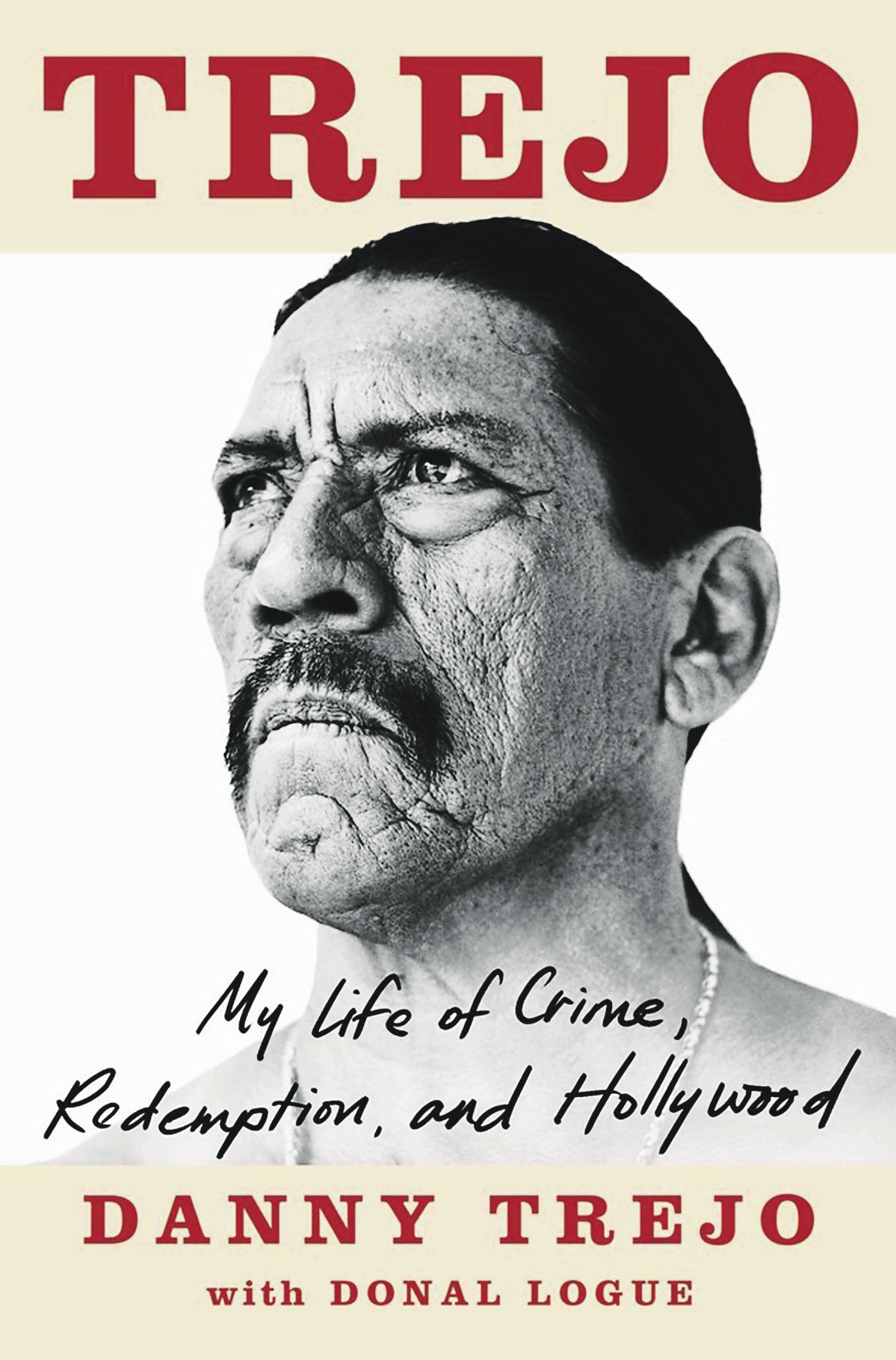

Some of these stories have been told; many have informed his wildly prolific work; and the most important are collected in his new memoir “Trejo: My Life of Crime, Redemption, and Hollywood.” In conversation, as perhaps on set, they flash across his face like involuntary tics.

“When I’m playing that insane, crazy person, I’ve been there, I’ve seen that,” Trejo said during a video interview from his home in Los Angeles. “I don’t want to be there. That place that you can go to is very, very real.”

A legendary Hollywood genre actor beloved for both his roles and his off-screen acts of selflessness, Trejo got his break in the business after visiting a film shoot in 1985 to help someone on-set who was battling through addiction recovery. He’d done it himself. Decades earlier, deep in the hole at Soledad state prison, Trejo had promised God he’d help his fellow human every day if he could “die with dignity.” And he had gone sober.

An assistant director stopped him that day on the set. “You have a good look,” the crew member said. “Can you play a convict?”

Funny question. He got hauled into a police station for the first time at age 10, he writes. From that point on, he spent years engaging in criminal mayhem in the San Fernando Valley and up and down the state, cycling through juvenile and state prisons and never expecting to come out alive. Could he play a convict?

As an extra in “Runaway Train” that year, Trejo stood out so much that he got a scene built around him, showing off boxing skills he’d honed in prison. In short order, he began appearing in a proliferation of shows and films as an archetypical supporting figure: Prisoner, 2nd Inmate and Tough Prisoner No. 1 are some of the roles he’s played since.

“I didn’t know I was being stereotyped,” Trejo told The Times. “I just knew I was working. And I think the fact that I was stereotyped for so long got a lot of people jobs, so we just opened the door.”

Trejo’s face, famously mangled by lived experience, offers an ideal expressive palette for the actor he became; he can convey rage and humor like few other villains on screen.

In 1995, Trejo shared a riveting death scene with Robert De Niro in Michael Mann’s “Heat,” one of many displaying Trejo’s uncanny skill at playing someone on the brink of expiring. “I’ve got the record for deaths in film,” he said. “It just means that I work a lot.”

Robert Rodriguez then gave him a signature role in “Desperado.” And in 2001, Rodriguez specifically created for Trejo the role of Machete in “Spy Kids,” which then recurred in a spinoff “Machete” series, establishing perhaps the only character in film history to straddle the genres of children’s adventure and grindhouse horror.

While the general arc of Trejo’s story is well known, many other formative details and wild intersections are revealed for the first time in the book, co-written with actor and longtime friend Donal Logue. The result is an often eye-popping personal narrative that belongs among the great California memoirs.

The reader is treated to a deep dive into barrio culture as it was lived in the Valley in the 1950s and 1960s. From an early age, he understands the true distance between the glitter of nearby Hollywood and his world of drug-dealing and bare-knuckle violence.

But during the course of Trejo’s life, those worlds also collide in staggering ways.

One crystallizing episode came when Trejo was weighing offers to appear in two films in the works in the early 1990s. One was “American Me,” to be directed by Edward James Olmos; the other was “Blood In, Blood Out” by Taylor Hackford. Both sought to tell the story of the founding of the Mexican Mafia.

It was a sensitive subject. Trejo, with his imposing physique and years of time served, would have been a great fit for either film. There was a problem, though. The Mexican Mafia, or “Eme,” is highly secretive, and notorious for its ruthless executions, according to federal cases.

Word already was getting around the penitentiary system that the “American Me” script took offensive narrative liberties — related to prison rape and the Eme’s fraternal codes — that were upsetting real-world gang leaders. The proposed film would explicitly use the term “Eme,” another no-no.

Seeking to cast Trejo, Olmos arranged for a meeting. Trejo showed up at Jerry’s in Encino as anyone might for a Hollywood sit-down, in casual business attire. Surprisingly, Olmos appeared in “full cholo wear,” Trejo writes, including a “blue shirt buttoned up at the top and flying open to the bottom.” Trejo says Olmos was trying to speak like an “OG from the streets” throughout their meeting.

“Everything was ‘theatrical’,” Trejo recalled of Olmos’ pitch. “And I said, ‘You’re not dealing with theatrical people here. You’re dealing with people who get mad and show up in the middle of the night.’”

Sure enough, just before a second meeting with Olmos, Trejo got a message: Joe Morgan wanted to talk.

Joe “Peg Leg” Morgan, incarcerated at the time, was then the living don of the Eme. “Joe Morgan doesn’t call people unless he’s saying, ‘You’re dead’,” Trejo said.

He took the call on the home phone of his friend Eddie Bunker, an industry insider he’d known since their time together in prison. Morgan got right down to business. He asked Trejo which movie he’d do; Trejo said he was leaning toward “Blood In.”

“I’ll never forget: ‘Oh yeah,’ Joe Morgan said, ‘The cute one,’ “ Trejo recalled with a laugh. Morgan approved the choice.

Thinking back on those early encounters with Olmos led Trejo to reflect on his struggles to be treated as an equal among Hollywood’s elites. “I’m going to tell you the truth,” he told me. “I don’t think Eddie Olmos has accepted me as an actor yet.”

Olmos did not respond to a request for comment about the passage. In the book, Trejo emphasizes his admiration for Olmos and his advocacy for Chicanos in Hollywood.

Logue, who grew up largely in the Calexico border region and first met Trejo on the set of “Reindeer Games” (2000), said in an interview that there was trepidation about detailing Trejo’s memories related to “American Me.”

“Edward James Olmos is a giant in our world” of moviemaking, Logue said. “What happened there was this interesting intersection with our world, which was one that frankly Danny always questioned his role in.”

Olmos, a highly respected industry veteran, made “American Me” as a morality play to warn youth about the dangers of prison life.

Yet the story’s ripple effects in the real world were unmistakable: Two consultants who worked on the film were killed, including a beloved gang intervention worker. Trejo contends that as many as 10 people were killed either in prison or outside the system in relation to working on “American Me.”

Trejo, for his part, took a smallish role in “Blood In, Blood Out,” an experience that allowed him to return to San Quentin for the first time since he was an inmate there, this time as an actor.

Worlds collided again. During filming, he writes, Trejo was able to roam almost freely inside a facility that for him was the site of so many horrors. Early passages in the book describe mortal dangers lurking around every corner at San Quentin.In a state of “full circle,” he even shot a few scenes inside C550, his former cell in the prison’s South Block.

His reflections in such key moments are finely rendered.

“You got to remember,”he said, “in 1968, I’d made a deal (with God). I said, ‘If you let me die with dignity, I’ll say your name every day and I’ll do whatever I can for my fellow inmates — and I said ‘inmates’ because I never thought I’d get out of jail.”

A year later he left prison for good. Despite many bumps along the road, Trejo transformed into a dedicated recovery counselor.

Throughout the book, certain figures loom large, chief among them his Uncle Gilbert, the man who Trejo says introduced him to a life of crime from a painfully young age. Logue, the co-author, said the various figures who filter in and out of the story each deserve their chronicle.

“If you go down a rabbit hole on all these different characters who are in Danny’s book, you see how violence begets generational violence,” Logue said. “Things will happen when we’re young that will set us off on this journey.”

A reader gets the sense that Trejo tempers what could have been harsher readings of many of those characters, including his parents. As the story progresses, the lives of his children become a central thread.

Women are ever present in Trejo’s book, from the earliest lines. He writes frankly about his mixed record with spouses, recalling that someone remarked he was the kind of guy who loved weddings except for the marriage part.

“I wasn’t great at drawing lines in my marriages, but I respected that line in recovery,” he writes at one point.

Recovery, ultimately, is the driving force of the memoir. Trejo, now 77, has more than 400 credits, according to IMDb, a remarkable achievement for someone who could hardly have imagined a film career as he prayed at Soledad in 1968.

“Acting wasn’t new to me,” Trejo writes. “I’d acted to survive my childhood. I’d acted like I wasn’t scared when I was terrified. In Folsom, I acted to keep my sanity. I had to move; I had to speak out loud; I had to hear my own voice.”

Today, he recognizes how far Hollywood has to go to expand opportunities — and roles beyond Tough Prisoner No. 1. On the topic of Latino representation, the subject of a recent series of stories in The Times, Trejo says he welcomes the growing advocacy. But what’s more plainly needed to move the needle, he argues, is more direct investment from high-powered producers of Latin American descent.

“People on top, Latin American people, do not want to produce films,” he said. “Somebody named Smith isn’t going to say, ‘I want a Mexican in the lead.’ Stop crying and start putting up some money!”

It may sound like tough love, but after reading the book and talking to the man, you come away with the sense that Trejo’s indomitable hardness serves a kinder philosophy. Trejo summarizes it in “Trejo,” in a maxim his life story bears out. “Everything good that’s ever happened in my life,” he writes, “has come as a direct result of helping someone else and not expecting anything in return.”

Daniel Hernandez writes for the Los Angeles Times.