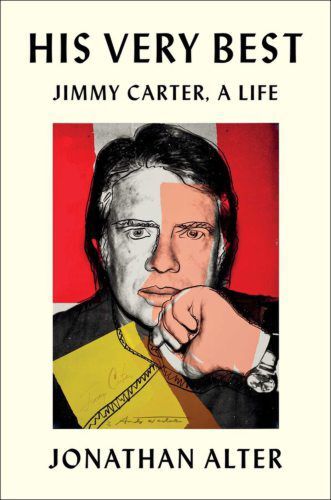

“His Very Best: Jimmy Carter, a Life” by Jonathan Alter; Simon & Schuster (782 pages, $37.50)

You might think you know the story of Jimmy Carter: Failed president, outstanding ex-president.

It’s a lot more complicated than that, as journalist and historian Jonathan Alter makes clear in “His Very Best: Jimmy Carter, a Life.”

Carter celebrated his 96th birthday in October, making him the longest-lived American president. It’s somewhat surprising that there has not been, until now, a thorough and authoritative biography of the 39th president.

Alter makes up that deficit, in style and substance. “His Very Best” is a deeply researched, carefully evenhanded and engagingly written journey through the life of a highly complex man. Although it’s clear Alter admires his subject, he doesn’t hesitate to address Carter’s faults and failures as well as his successes, to give us a fully developed portrait of the man in his historical context.

Alter has written three best-selling books about presidents, one about Franklin Roosevelt and two about Barack Obama. “His Very Best” is a full-fledged biography, based on several hundred interviews (including more than a dozen with Carter) and countless documents.

The book delves in detail into Carter’s childhood in rural Georgia, where the boy was shaped by his parents: Demanding, conservative Earl and adventurous, liberal (for the time and place) Lillian. Carter’s prodigious work ethic and deeply felt religious faith grew from these earliest days.

Second to Carter himself, the most dominant figure throughout the book is his wife, Rosalynn. The two met when Jimmy was 3 years old, a couple of days after Miss Lillian, who was a nurse and midwife, delivered Rosalynn. Jimmy didn’t notice her much until he came home on leave from the Naval Academy and was smitten by the 18-year-old beauty.

Alter documents their long (74 years and counting) and deeply interdependent marriage. Independent, outspoken and perceptive, Rosalynn deserves a biography.

The book covers Carter’s years at Annapolis, his Navy career and his relationship with Adm. Hyman Rickover, one of the biggest influences on his life. (The book’s title comes from a question Rickover asked Carter.) Carter had high military ambitions, particularly after Rickover put him on the team developing nuclear submarines, but his father’s death led him to resign and return to Plains, Ga., to run the family businesses.

That didn’t satisfy him for long. Alter relates his run for the state legislature and, in short order, the governor’s mansion. That victory signaled a turning point in Carter’s stance on race. Although his win was aided by support from outright racists like Lester Maddox and George Wallace, in his inaugural speech he shocked Georgians by declaring that “the time for racial discrimination is over.”

Alter’s recounting of Carter’s presidential run is fascinating. It began almost as soon as Carter was elected governor of Georgia, even though he was unknown to most of the nation. Assisted by a young, irreverent cadre of campaign advisers, he was the first presidential candidate to emphasize the Iowa caucuses, and he became the first to voluntarily release his tax returns, setting a standard that every subsequent candidate would meet, save one.

Carter’s friendships with musicians like Bob Dylan and Gregg Allman drew younger voters. One of the biggest factors in his narrow victory over Gerald Ford was his outsider status — after the crimes and corruption of the Watergate scandal, many voters longed for someone untouched by Washington. Carter’s promise to Americans that he would not lie to them might have been a tad optimistic, but it resonated.

“If there is a gene for duty, responsibility, and the will to tackle messy problems with little or no potential for political gain,” Alter writes, “Jimmy Carter was born with it.” His presidency was evidence.

The first president to make the environment a key concern, Carter installed a solar water heating system in the White House and proposed $1 billion in federal funding for solar power research. His admonitions to turn down thermostats to save energy were fodder for comedians, but made a point.

Carter brought human rights to the forefront in U.S. foreign policy. He appointed unprecedented numbers of women and minorities to federal courts and increased diversity throughout the government. Alter offers a remarkably detailed account of Carter’s signature achievement, the Camp David Accords between Israel and Egypt.

But those achievements were often overshadowed by other problems that shaped public opinion; his favorability ratings as president ranged from 75% to 28%. When he took office in 1977, Carter inherited a dismal economy, plagued by high rates of inflation and unemployment and soon escalating into an energy crisis.

Then there were the unforced errors. Alter describes the interview with Playboy magazine in which Carter said that although he didn’t cheat on his wife he sometimes “lusted in his heart” over other women. These days that seems almost quaint, but at the time it threw the whole country into a swivet.

When Islamic radicals raided the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, Iran, in 1979, taking 52 Americans hostage, it sparked a crisis that lasted for more than a year despite Carter’s intense diplomatic and military efforts. The hostages were not released until Jan. 20, 1981, minutes after new President Ronald Reagan completed his inaugural address.

As always, though, the resourceful Carter came up with a Plan B. In 1982, Alter writes, Carter woke in the middle of the night with a map for the rest of his life. His presidential library would not be a repository of documents and mementos for tourists; it would be a center for global activism, led by him and Rosalynn.

Like so many things in Carter’s life, it didn’t go entirely smoothly — the location chosen for the center was highly controversial in Atlanta. But Carter got it built, and the Carter Center has been involved in projects around the globe to fight famines, monitor elections and promote democracy. Perhaps its greatest success, one the Carters led, was “jaw-dropping progress” in controlling Guinea worms, a harmful parasite common in Africa. “When Carter first focused on Guinea worm in 1986,” Alter writes, “the disease afflicted 3.5 million people. By 2014, it was down to 130 cases worldwide.”

In 2002, Carter won the Nobel Peace Price for a lifetime of achievements. He has published 32 books; well into his 90s, despite major health crises including cancer and broken bones, he helped build houses for Habitat for Humanity and taught Sunday school classes in Plains, where he and Rosalynn live.

They are housebound there now by another global health crisis, Alter writes. Carter has “come full circle” after “constantly reimagining himself and what was possible for a barefoot boy from southwest Georgia with a moral imagination and a driving ambition to live his faith.”

Colette Bancroft writes for the Tampa Bay Times.