So far, this has been a really good century for nerds, with lots of jobs, higher pay and an abundance of promotions. Then there’s the admiration we get, however reluctant it might seem, in almost every TV show and a multitude of movies. With the exception of medieval dramas, there’s a resident nerd in every show.

The last century was pretty good, too.

Clearly, the Age of Nerds has arrived.

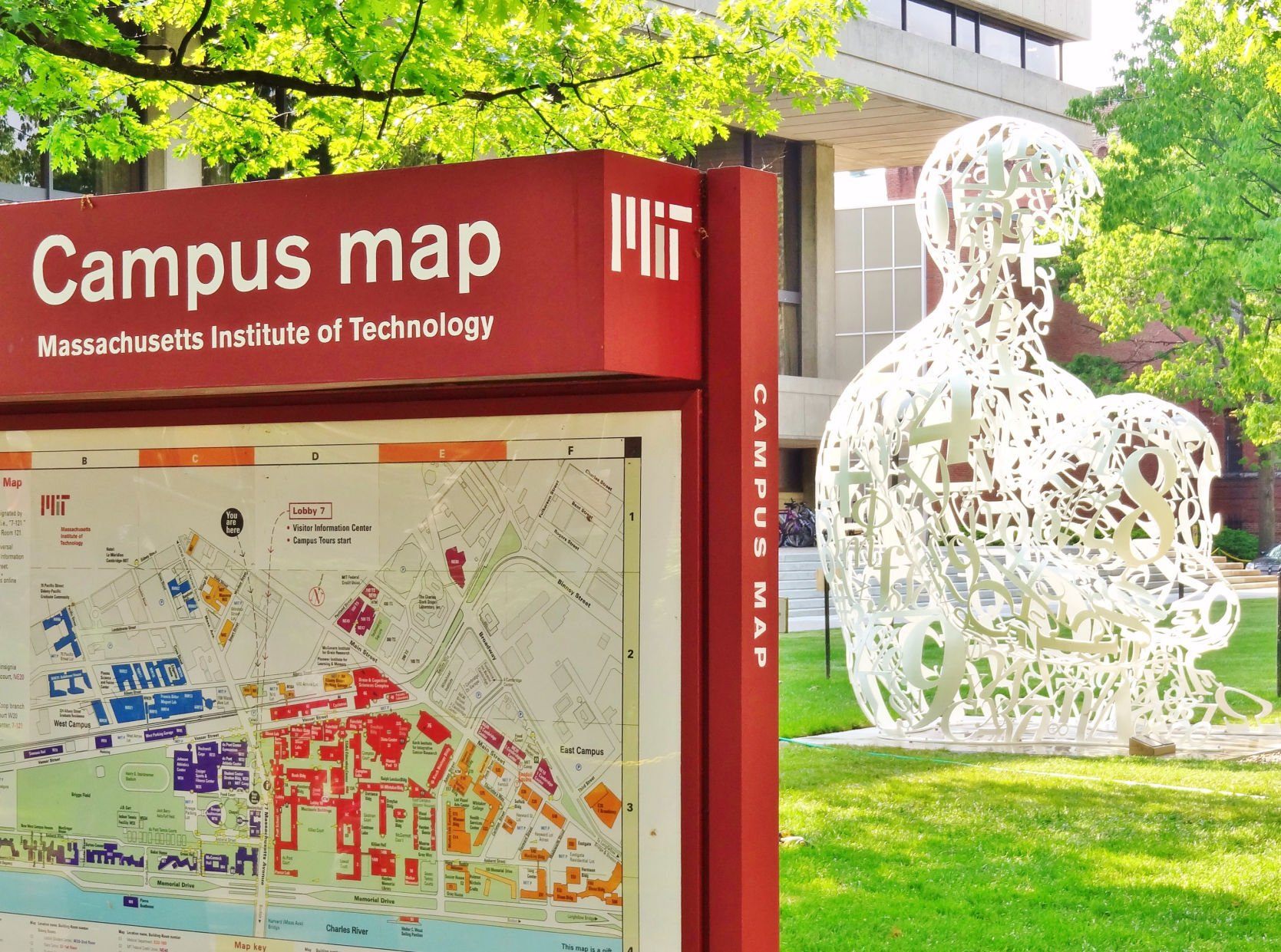

This was evident at a recent gathering at my alma mater, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Gray, if not white, hair prevails for the class of 1962. Our 60th reunion was part of Technology Day at the end of May.

I wasn’t there with my classmates. I was in Annapolis awaiting a new suit of sails for my boat. But I had already obtained the newest data. It tells me that this truly is the Age of Nerds. Better still, the reward is way better than mere money. Or ephemeral prestige.

It’s longevity. The blessing of a longer life.

More life, per life

Just as an earlier measure showed that my classmates were failing to die as rapidly as their age cohorts were back in 2016, the current measure continues the trend. While a typical member of the class of 1962 is about 82 years old, the survivorship of our class more closely resembles a group of men who are about 72.

Here are the basics. According to Institute figures, of 840 graduates in the class of 1962, 234 have died. An additional 18 are missing. But if we take the most basic figure, the 234 who have died of 840 graduates, we learned that an amazing 72% of those 22-year-olds have survived. Adding the missing, who might be assumed dead, doesn’t change the percentage greatly.

In comparison, the most recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention life tables inform us that of every 100,000 non-Hispanic White males born, 98,765 could be expected to survive to age 22 but only 45,723 could expect to live to 82. That’s only 46%.

If you’re wondering why I used the life table for non-Hispanic White males, rather than a table for all males or a joint male and female table, the reason is simple. In 1962, women were a trace element at MIT. And almost all the men were White.

You can delay death, but you can’t escape it

Please note that living longer should not be confused with immortality. Vast wealth and philanthropic contributions to medical research notwithstanding, my classmate David Koch, the co-owner of Koch Industries, was one of the 234 who didn’t make it. The distinction for the MIT class of 1962 is that we are departing more slowly than most humans.

Fortunately, you don’t have to go to MIT to enjoy this blessing. If you persevere and get a good education and earn a higher-than-average income, you’re likely to live a longer life. I believe it will work nicely for our grandchildren who have, or will, graduate from Texas A&M and UT.

Why am I so confident?

Simple. Every bit of research since the original Whitehall studies on longevity indicates that people with college degrees and high incomes are likely to live a longer and healthier life than those with less education and less income.

The original Facebook

That reality turns into really good news when you compare the class of 1962 with current and coming graduating classes at MIT (and elsewhere). Sixty years ago, very few women went to MIT.

The Institute (or the Gray Pile on the Charles, as some called it) was all yang and no yin.

Our version of Facebook was a copy of the coveted annual printed directory, with pictures, of the new women at Radcliffe, then the college for women at Harvard, several miles away.

Today, nearly half of all MIT undergraduates are women. And women now account for more than 50% of undergraduates at all colleges. So the past 60 years have seen a seismic shift. At last, the full pool of human talent is being developed.

It’s not just White guys anymore. It’s both sexes, some non-binaries and significant percentages of Asian, Hispanic, Black and mixed-race students.

In a news year that’s desperately short on hope, I just love this. It’s good will toward all.

Scott Burns is the creator of Couch Potato investing and a longtime personal finance columnist for The Dallas Morning News.