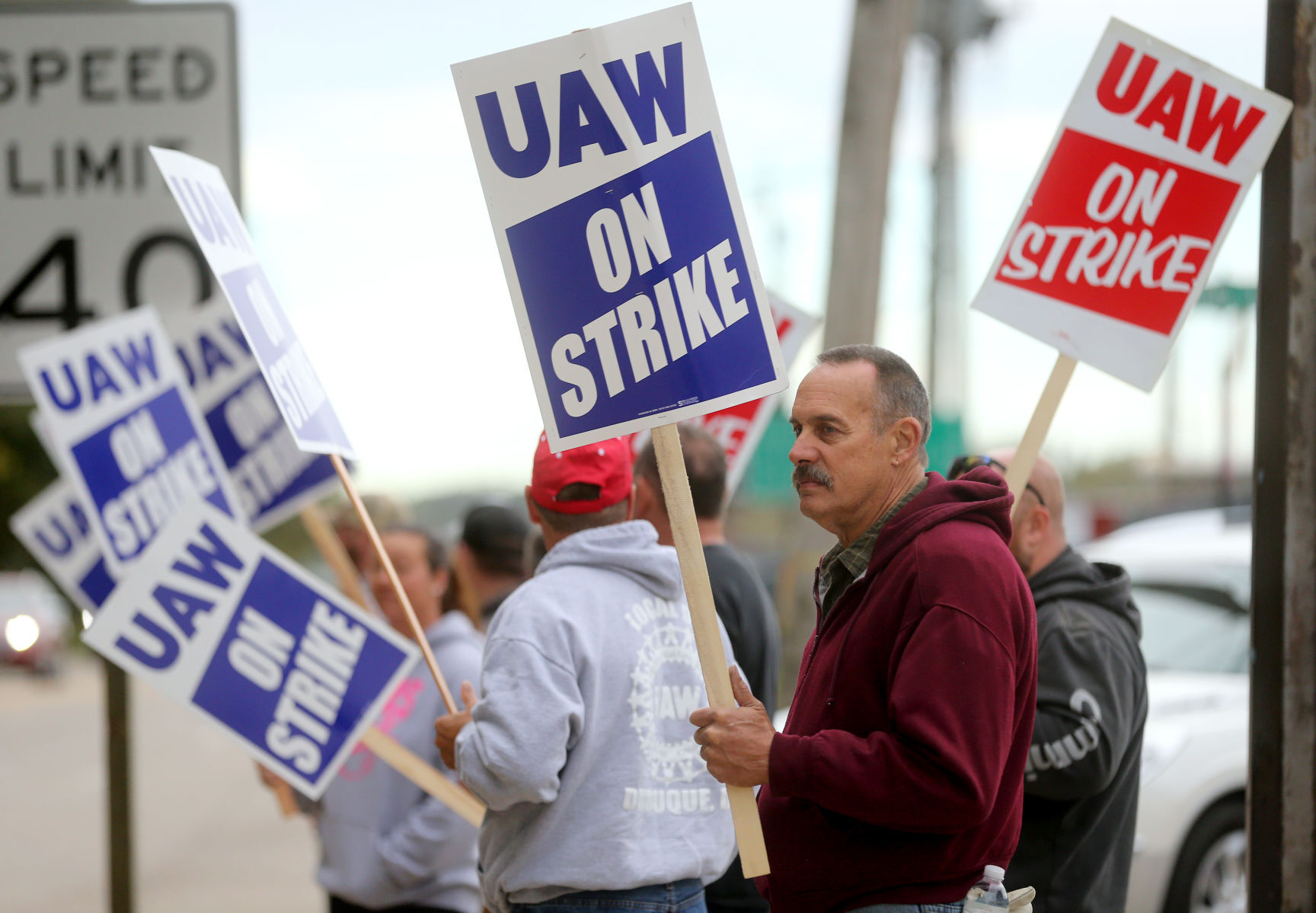

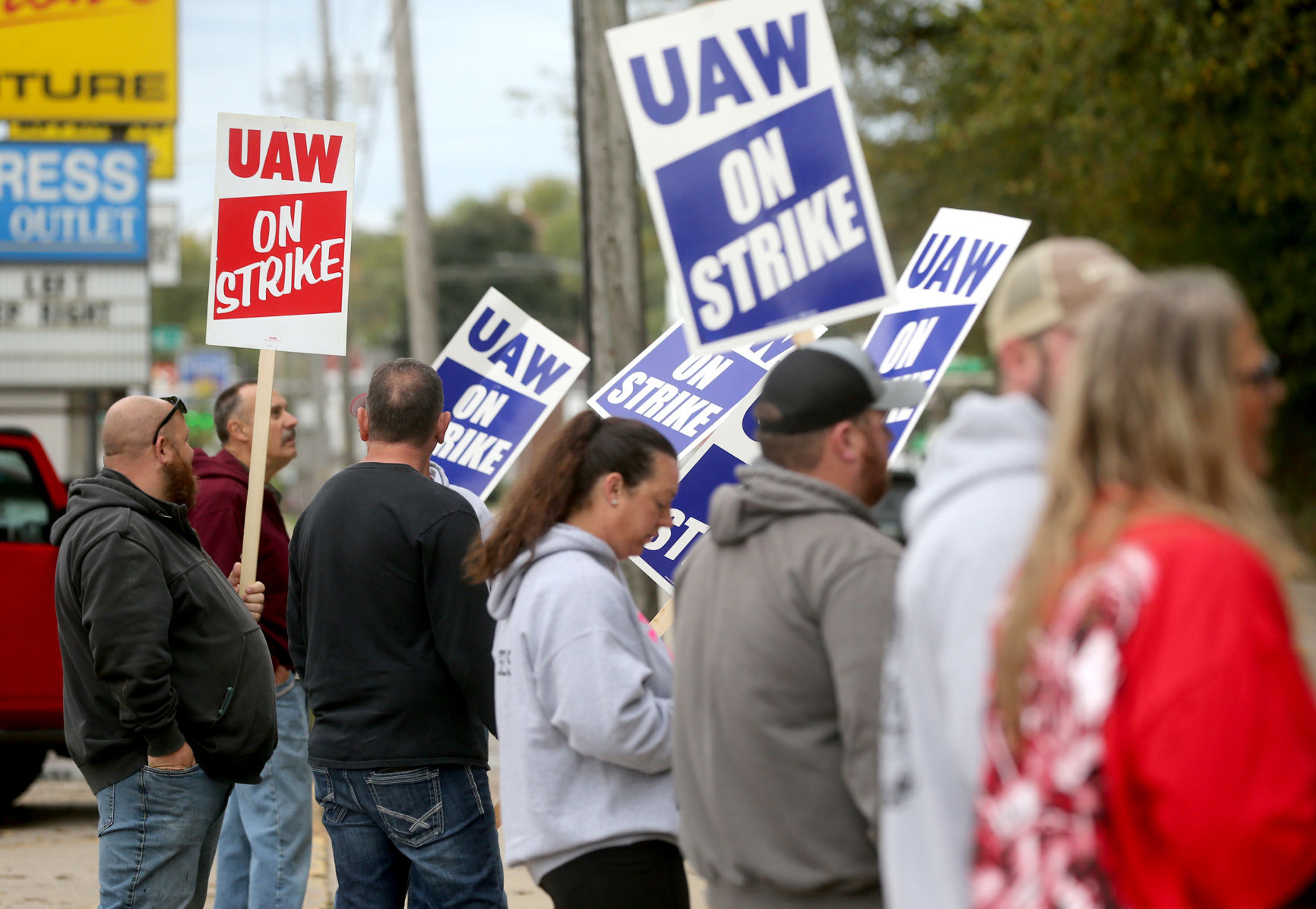

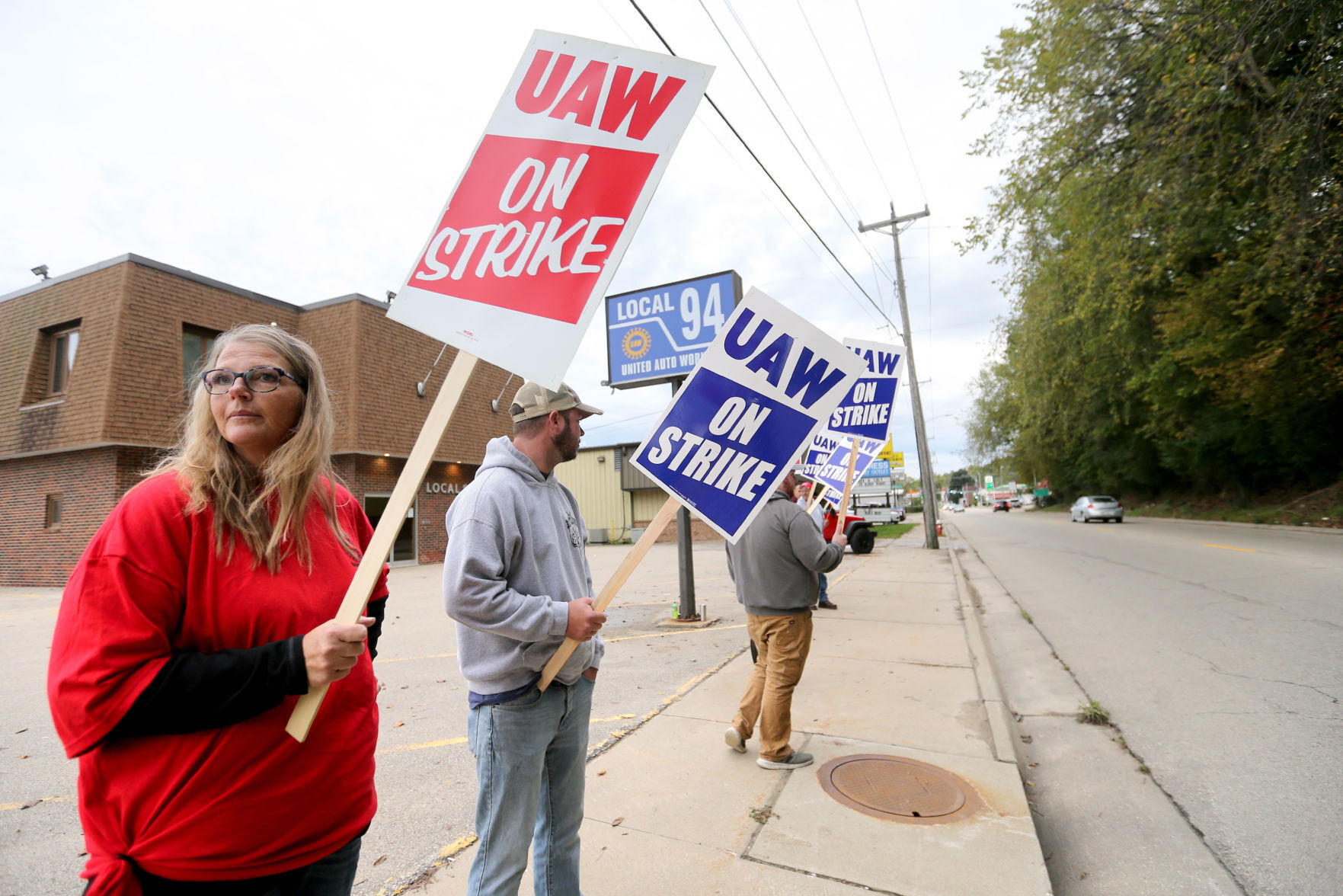

Dozens of union members from John Deere Dubuque Works gathered at strategic locations Thursday to rally support for their strike.

Picketers convened at multiple entrances to the Dubuque plant, holding signs. Members also gathered outside the United Auto Workers Local 94 Hall on Central Avenue.

Mark Lyons, an assembler at Dubuque Works, said he woke up at 4 a.m. so he could “join his brothers and sisters on the line” as early as possible. He was part of a group gathered outside the south entrance to the Dubuque Works plant.

Lyons emphasized that many union members believe this strike could have ripple effects that last for decades.

“We are looking for better working conditions and better benefits for ourselves and for future generations,” he said. “It’s not just about us. It is also for the workers of the future.”

John Deere Dubuque Works employs 2,800 workers — making it Dubuque County’s largest employer — although not all of them are union members.

The contract between UAW and Deere covers more than 10,000 production and maintenance workers at about a dozen facilities, including plants in Iowa, Illinois, Kansas, Colorado and Georgia.

The union’s previous six-year contract was originally set to expire on Oct. 1. UAW and Deere reached a tentative agreement on the first day of October, but the proposal was rejected by 90% of UAW members on Sunday. A final strike deadline of 11:59 p.m. Wednesday came and went without a new agreement, resulting in the first major strike staged by John Deere workers since 1986.

STRIKE BEGINS

Steve Thor has worked at Dubuque Works for four years, focusing on machine maintenance. He started his shift on the picket line at 8 a.m. Thursday, setting up camp outside the labor hall.

Many passing motorists sounded their horns in a demonstration of support, bringing a smile to Thor’s face.

“It is encouraging to hear the honking,” he said. “It is nice to feel that support.”

Thor believes the strike was justified, noting that Deere has reported strong earnings in recent years and arguing that the success should trickle down to the factory workers.

The company reported net income of $4.7 billion through the first three quarters of the current fiscal year, easily eclipsing the $2 billion reported through the first nine months of the previous fiscal year.

Thor acknowledged that there could be a long road ahead.

“I think it could take awhile to get this hammered out,” he said. “We’ll just have to wait and see what happens.”

He noted that many union members were preparing for the strike for months.

“We’ve tried to plan ahead and build a little (financial) cushion, so you have enough to get by,” he said. “The bills don’t stop.”

UAW member T.J. Nelson also spent part of his morning picketing outside the UAW hall.

Nelson said the strike seemed like a foregone conclusion after Sunday’s vote. He said that offer didn’t sit well with workers who have toughed out the COVID-19 pandemic over the past couple years.

“We were deemed essential workers during the pandemic,” he said. “It didn’t seem like the contract they offered us in bargaining treated us like we are essential.”

MAJOR IMPACT

Deere & Co. said Thursday that the affected plants are not shut down. In a statement, the company indicated that “employees and others will be entering our factories daily to keep our operations running” but provided no further details on these plans. Deere & Co. Director of Public Relations Jen Hartmann told the Telegraph Herald that she could not provide more specifics on the initiative.

UAW spokesman Brian Rothenberg did not return a call placed by the TH on Thursday.

Rick Dickinson, president and CEO of Greater Dubuque Development Corp., emphasized that Deere plays a critical role in the local economy.

“Any community would be blessed to have John Deere Construction and Forestry and the talent of UAW Local 94 as a part of their corporate family,” he said.

Dickinson noted that Deere employs 5% of the total workforce in the county. Additionally, many local businesses supply parts and materials to Deere or otherwise serve the plant, potentially creating what Dickinson called an economic “ripple effect.”

Dickinson declined to comment on the specifics of ongoing negotiations but expressed his wish for a swift conclusion.

“I am hoping for expeditious and successful negotiations between all parties,” he said.

Economic experts believe recent economic shifts could alter the trajectory of these talks.

Loren Rice, an associate professor of accounting and business at Clarke University in Dubuque, noted that unions generally have been losing leverage in negotiations over the course of the past quarter-century. This is due largely to the fact that workers have more to lose.

“Typically, the owners have huge advantages,” he said. “During a strike, the business is only losing profit. The workers are losing their paycheck.”

But Rice said this dynamic has been turned upside down in recent years, due largely to the worsening workforce shortage facing employers. As a result, business owners might perceive a strike differently.

“There are not any workers to take their place,” Rice said. “For the first time in several decades, the union has a real advantage.”

Iowa State University economist Dave Swenson said its strong earnings give Deere the means to come to terms with workers.

“They can afford to settle this thing on much more agreeable terms to the union and still maintain really strong profitability,” he said.

Swenson said the impact of the strike could spread further if companies that supply Deere factories have to begin laying off workers. Deere will face pressure from suppliers and from customers who need parts for their Deere equipment to settle the strike quickly. And Swenson said Deere will be worried about losing market share if farmers decide to buy from other companies this fall.

“There is going to be a lot of pressure on Deere to move closer to the union’s demands,” Swenson said.

ADDRESSING THE GAP

As the strike deadline approached, local union members were angry at both the company and the union leadership. A union steward from John Deere Dubuque Works told the TH that local members were “angry with the UAW International for even considering” Deere’s initial offer.

Only 10% of union members voted to accept that deal.

According to Deere officials on Thursday, the typical production employee’s all-in annual wages — a figure that also factors in components like overtime and profit sharing — would have increased from $60,000 today to $72,000 by the end of the proposed six-year agreement. This equates to an hourly increase from about $33 per hour to nearly $40 per hour, the company said.

However, multiple local Dubuque Works union members said those wage ranges are much higher than what they make, and they disputed the figures being shared by the company.

Company officials expressed hope that common ground can be found soon.

In a statement sent to the TH on Thursday, Deere officials reiterated that the company is “committed to reach an agreement with the UAW that would put every employee in a better economic position and continue to make them the highest-paid employees in the agriculture and construction industries.”

In the meantime, Deere is troubleshooting new ways to stay afloat.

The company announced the activation of its Customer Service Continuation Plan, an initiative that aims to find short-term solutions to production needs at a time when union members are on strike.

“Our immediate concern is meeting the needs of our customers, who work in time-sensitive and critical industries such as agriculture and construction,” the statement reads. “By supporting our customers, the CSC Plan also protects the livelihoods of others who rely on us, including employees, dealers, suppliers and communities.”