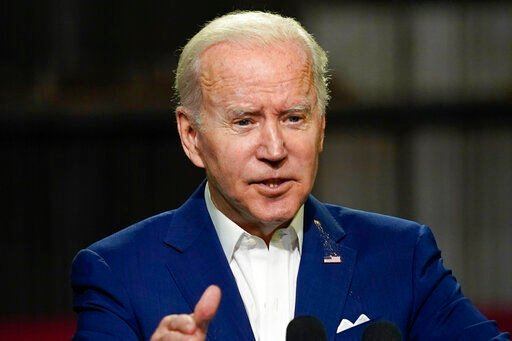

WASHINGTON — One year ago, Joe Biden marked his first Earth Day as president by convening world leaders for a virtual summit on global warming that even Russian President Vladimir Putin and China’s Xi Jinping attended. Biden used the moment to nearly double the United States’ goal for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, vaulting the country to the front lines in the fight against climate change.

But the months since then have been marred by setbacks. Biden’s most sweeping proposals remain stalled on Capitol Hill despite renewed warnings from scientists that the world is hurtling toward a dangerous future marked by extreme heat, drought and weather.

In addition, Russia’s war in Ukraine has reshuffled the politics of climate change, leading Biden to release oil from the nation’s strategic reserve and encourage more drilling in hopes of lowering sky-high gas prices that are emptying American wallets.

It’s a far cry from the sprint toward clean energy that Biden — and his supporters — envisioned when he took office. Although Biden is raising fuel economy standards for vehicles and included green policies in last year’s bipartisan infrastructure legislation, the lack of greater progress casts a shadow over his second Earth Day as president.

Biden will mark the moment on Friday in Seattle, where he’ll be joined by Gov. Jay Inslee, a fellow Democrat with a national reputation for climate action. Biden also is scheduled to visit Portland, Ore., today as part of a swing through the Pacific Northwest, a region that has often been on the forefront of environmental efforts.

Administration officials defend Biden’s record on global warming while saying that more work is needed.

“Two things can be true at the same time,” said Ali Zaidi, the president’s deputy national climate adviser. “We can have accomplished a lot, and have a long way to go.”

Zaidi acknowledged that “we have headwinds, we have challenges,” but also said the president has “a mandate to drive action forward on this.”

Kyle Tisdel, climate and energy program director with the Western Environmental Law Center, said Biden has not lived up to the promise of last year’s Earth Day summit.

“Climate action was a pillar of President Biden’s campaign, and his promises on this existential issue were a major reason the public elected him,″ Tisdel said. ”Achieving results on climate is not a matter of domestic politics, it’s life and death.”

Biden had hoped to pass a $1.75 trillion plan for expanding education programs, social services and environmental policies. But Republicans opposed the legislation, known as Build Back Better, and it failed to get the unanimous support necessary from Democrats holding a slim majority in the Senate.

The final blow came from Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., who owes his personal fortune to coal and represents a state that defines itself in large part through mining that fossil fuel. Democrats hope to revive the bill in some form, but it’s unclear exactly what Manchin would support, putting any possible deal in jeopardy.

White House press secretary Jen Psaki said this week that negotiations were ongoing even though Biden wasn’t publicizing them. “Just because he’s not talking about it doesn’t mean those conversations are not happening behind the scenes,” she said.

Administration officials are expected to speak Saturday at a rally outside the White House as climate, labor and social justice groups urge Congress to pass climate legislation before Memorial Day. Similar events are planned in dozens of cities as activists stress the need for major investments to boost clean energy and create jobs.

The White House wants to win approval for more than $300 billion in tax credits for clean energy that advocates describe as crucial for meeting Biden’s goal of reducing emissions by up to 52% from 2005 levels by 2030.

Without the tax credits, “I don’t see a pathway,” said Nat Keohane, a former Obama energy adviser who is now president of the independent Center for Climate and Energy Solutions. Reaching the midterm elections in November without them “would amount to a failure on the promise of the first year,” he said.

Asked if Biden’s goal of reducing emissions is still achievable, Psaki said, “We are continuing to pursue it, and we are going to continue to do everything we can to reach it.”

Psaki noted that the $1 trillion infrastructure law includes an array of climate policies, including funding for the construction of 500,000 electric vehicle charging stations. However, an analysis by the consultancy McKinsey estimates that nearly 30 million chargers are needed by 2030.

The Ukraine war has worsened the political challenges at home by sending shockwaves through global energy markets and increasing gas prices.

It’s also caused Biden to change his tune on oil drilling. Last week, Biden moved forward with the first onshore sales of oil and gas drilling leases on public land, a move that environmental groups blasted even though the administration said it was only doing so under a court order.

Although the legal battle is ongoing, in the meantime Biden is encouraging new domestic production.

“The bottom line is if we want lower gas prices we need to have more oil supply right now,” Biden said in March.

The leasing plan “is an ugly betrayal of Joe Biden’s campaign promises and his administration’s rhetoric on environmental justice and climate action,″ said Collin Rees, U.S. political director at Oil Change International.

“Biden is choosing to stand with polluters over people at the expense of frontline communities and the future of the planet,” he added.

The war in Ukraine has also frustrated diplomatic efforts to address climate change.

John Kerry, Biden’s international climate envoy, has focused much of his efforts on prodding China, the world’s top consumer of coal, to transition to clean energy more quickly. But that work “is harder now” amid China’s defense of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Kerry said Wednesday.

“Some of the differences in opinion between our countries have sharpened and hardened, and that makes diplomacy more difficult,” he said during an online discussion on climate finance with the Center for Global Development.

Kerry’s aides have downplayed talk he might leave the administration now that he’s served more than a year, and he remains a loyal defender of Biden’s climate efforts. But his tone has become more pessimistic recently, especially as Biden’s climate proposals remain stalled in Congress.

The administration was also rattled by recent reports that Biden’s domestic climate adviser, Gina McCarthy, plans to step down. McCarthy called the reports “simply inaccurate” and said she is “excited about the opportunities ahead.”

Another one of Biden’s climate-related efforts could divide the environmental community. His administration plans to offer $6 billion in funding to prevent financially distressed nuclear power plants from closing. Although the facilities produce carbon-free electricity, they’re viewed warily by some activists because of concerns about how to dispose of nuclear waste and the potential for devastating accidents.

“We’re using every tool available to get this country powered by clean energy by 2035,” Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm said in a statement.

Abigail Dillen, president of the environmental group Earthjustice, said that “spirits have dimmed” after the failures of the past year. Although she praised some of the policies that Biden has achieved so far, she said that “it’s not at the scale of climate action we need — full-stop.”

Now Republicans are poised to retake control of at least one chamber in Congress in November’s midterm elections, meaning there’s a limited window for making progress. Dillen and some other activists have suggested that Biden declare a climate emergency and use the Defense Production Act to boost renewable energy.

“It’s time to pull out all the stops,″ she said.