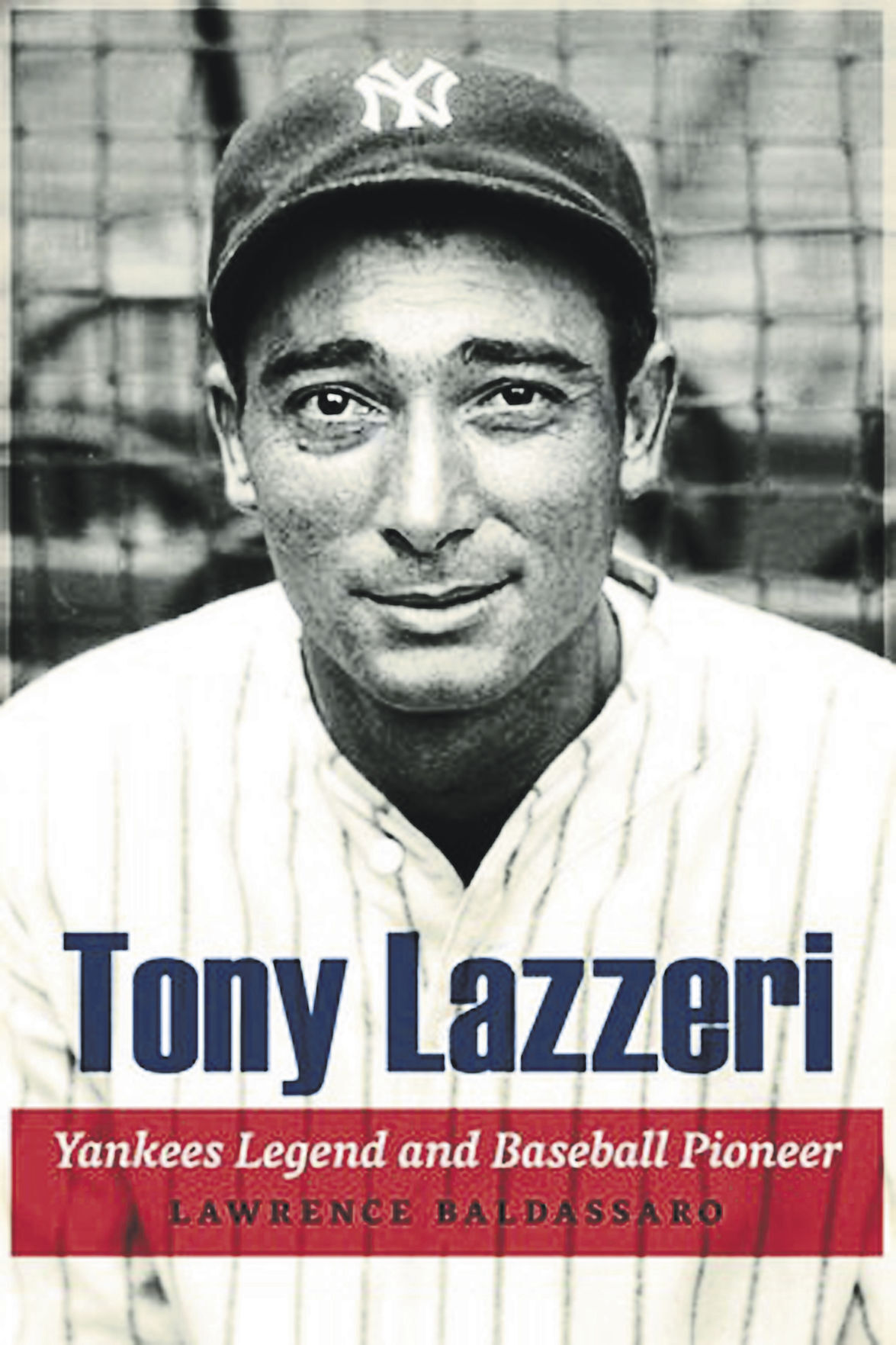

“Tony Lazzeri: Yankees Legend and Baseball Pioneer” by Lawrence Baldassaro; University of Nebraska Press (352 pages, $34.95)

Before DiMaggio, there was Lazzeri.

A home run hero, Tony Lazzeri was essential to the Yankees’ legendary Murderers’ Row. A son of immigrants, he broadened the game’s appeal and gave millions of Italian-Americans a role model.

He was a shy, serious gentleman who did this while enduring revolting bigotry and secretly battling a serious medical condition.

Lawrence Baldassaro’s “Tony Lazzeri: Yankees Legend and Baseball Pioneer” tells the story, and it’s one too many have forgotten.

Lazzeri’s parents, Agostino and Giulia, left Genoa poor in 1903. On the ship’s manifest, Agostino’s occupation was listed as “peasant.” The couple settled in San Francisco, and by the end of the year, had a son.

Life was not easy.

“I guess I was a pretty tough kid,” Tony Lazzeri said later. “The neighborhood wasn’t one in which a boy was likely to grow up to be a sissy, for it was always fight or get licked, and I never got licked.”

When he was 15, Lazzeri’s high school “invited” him to leave. It was no surprise.

“I boxed, played ball and did everything but study,” he admitted. “I guess I would have been kicked out of school long before I was had it not been for the fact that I pitched for the school team.”

He dropped out and joined his father working in an iron foundry.

“My pitching stood me in good stead,” he joked. “I could toss a rivet with the best of them.”

The teenager didn’t give up on baseball, though. When he was 18, he landed a tryout with the minor league Salt Lake City Bees. The job paid $250 per month. Lazzeri held on to his ironworkers’ union card. He’d hold on to it even after he made it to the majors, just in case.

Lazzeri’s first years in the minors were rocky, bouncing around, playing for outfits like the Peoria Tractors. But slowly, he settled in, his game growing more consistent. He settled down, too, marrying a former teammate’s sister.

Soon, the Lazzeri, who used to thrill them on San Francisco playgrounds, was back. By the end of the 1925 season, playing for the Bees, he hit 60 home runs — a minor league record. The Major Leagues were becoming interested.

There were only two problems.

First, anti-Italian prejudice ran high. Second, Lazzeri had epilepsy, a secret he managed to keep from fans but that plenty of coaches and managers knew. And lots of them didn’t want an Italian or an epileptic, playing the great American game.

However, Yankees general manager Ed Barrow didn’t care.

Lazzeri’s ethnicity? Italians weren’t exactly unknown in New York; by the mid-1920s, about 1 million Italians called New York home. Barrow figured having an Italian on the team might even sell tickets. With the Yanks heading to an embarrassing seventh-place finish that year, they needed all the fans they could get.

Lazzeri’s epilepsy? It already had scared off the Cincinnati Reds and the Chicago Cubs. But Barrow looked into it and found Lazzeri’s seizures usually happened in the morning. “As long as he doesn’t take fits between three and six in the afternoon,” Barrow decided, “that’s good enough for me.”

On Aug. 1, 1925, the team signed Lazzeri. His salary was $5,000.

The 22-year-old arrived in New York for the 1926 season with a new nickname, “Poosh ‘Em Up,” reportedly inspired by an old Italian fan’s call for a home run. Lazzeri also entered Yankee Stadium with more than the usual trepidation. Not only had he never played in the major leagues — he had never even seen a major league game.

If the rookie was stressed, though, he didn’t show it. Lazzeri played all 155 games that season and batted in 117 runs, second only to the team’s star, Babe Ruth. Lazzeri also emerged as the team’s de facto captain, keeping up morale and calming nervous performers like Lou Gehrig. That year, the Yankees won the pennant.

Although Lazzeri struck out in his final at-bat in the series, with bases loaded — to his eternal embarrassment — the general manager didn’t care.

“In our comeback from a calamitous seventh-place finish to a championship in 1926, there is one man who stands out above all others,” Barrow wrote later. “Tony Lazzeri. He was the making of that ball club, holding it together, guiding it and inspiring it. He was one of the greatest ballplayers I have ever known.”

The following season, the Yankees would become one of the greatest ball teams ever known.

Their lethal batting lineup — Earle Combs, Mark Koenig, Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Bob Meusel and Lazzeri — was dubbed Murderers’ Row. Their only true competition was themselves. Ruth matched Lazzeri’s minor league record by pounding out 60 home runs. Lazzeri set a Yankee record by homering three times in a single, regular-season game. Ruth then matched it the next season.

When it was time for the 1927 World Series, the Yankees pummeled the Pittsburgh Pirates 4-0.

Then, to prove this wasn’t a fluke, the Yankees came back in 1928 and swept the Cardinals, too.

But personally, things remained difficult for Lazzeri. Although he became an idol among Yankees fans and Italian-Americans across the country, his heritage was routinely insulted on the field and in the newspapers. And, of course, he continued to battle epilepsy, a condition exacerbated by stress and treated with phenobarbital, a drug that slowed his reaction time.

Lazzeri faced it as he faced everything — without complaint. He remained a steadying presence on the team, calming veterans and welcoming rookies, particularly Northern California Italians like Joe DiMaggio. And he indulged his schoolboy sense of humor, such as nailing teammates’ cleats to the locker room floor.

In 1935, Lazzeri set a record – hitting six home runs in three consecutive games. This record held until 2002 when the Dodgers’ Shawn Green broke it.

Lazzeri often played injured, and his performance had been uneven for years. “The consensus was that he was burned out and nearing the end of the road,” Baldassaro writes.

The second basemen himself seemed to agree. “I think I am good for another two or three seasons, but I don’t want to play anymore, and I won’t,” he announced in 1937. A managing job would be great, but if that didn’t happen, it was OK. “I’ve saved my money,” he added.

It was good he had.

After he left the Yankees in 1937, Lazzeri went to the Cubs as a coach and utility outfielder. Abbreviated seasons with the Dodgers and the Giants followed. Nothing clicked. Finally, it was back to the minor leagues, where he managed the Toronto Maple Leafs and played for his old hometown San Francisco Seals.

By 1943, his career was over. Three years later, he was found in his home, at the bottom of a staircase, dead at 42. The exact cause is debated.

Fans mourned. Many sportswriters mentioned his up-and-down career, with the Washington Post’s Shirley Povich writing that his World Series strike out had left Lazzeri “famed more for one failure than all the heroics he compiled.” But Barrow, the man who hired him, said it simplest and best: “One of the greatest Yankees of them all.”

Jacqueline Cutler writes for the New York Daily News.